CMU students raise awareness of fatal disease in deer

When Emily Rutkowski had to start brainstorming topics for her semester-long group project in her Recreation, Parks and Leisure Services 216 class, she suggested an idea that was important to her. Rutkowski’s fellow classmates agreed to spend the semester raising awareness for the chronic wasting disease, an affliction that only recently appeared in Michigan.

“I had an interest in it just because it was a narrow topic and a new problem in Michigan,” Rutkowski said.

Chronic Wasting Disease is a neurological affliction that affects deer, moose and elk. The disease is spread by prion proteins in the sick animal. These prions can be spread through general interaction between deer, such as grooming, and can be found in urine and feces, spreading the disease through the environment. The disease can also contaminate an area through decomposing remains of the animals.

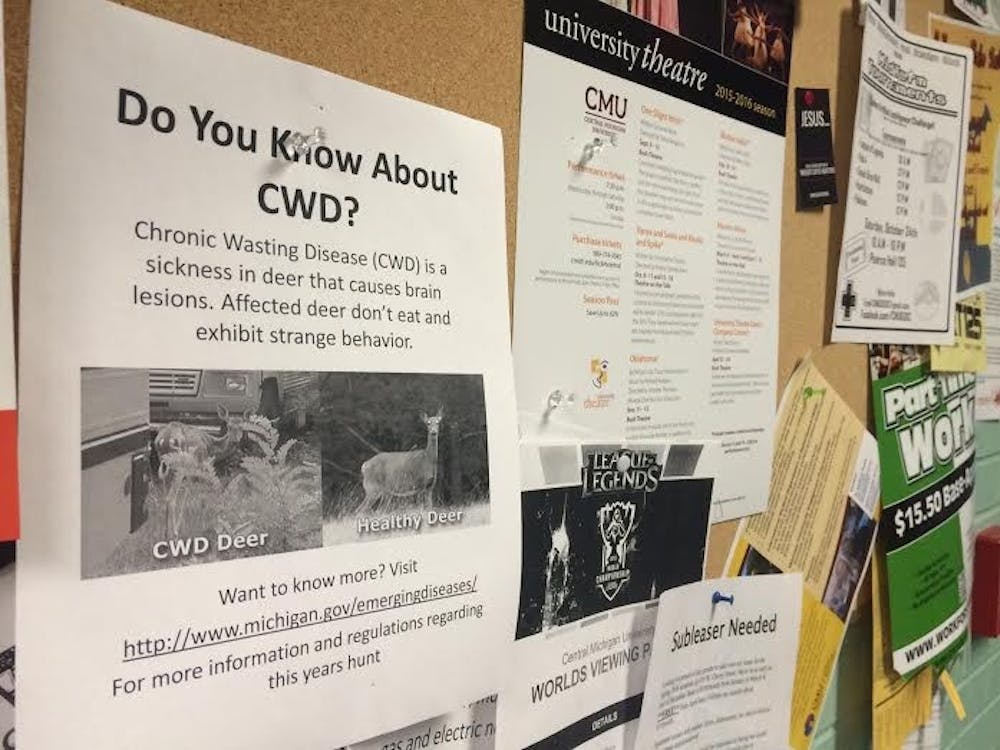

The group began hanging up posters around Brooks Hall encouraging students to keep an eye out for deer behaving oddly and asking hunters to have their deer checked by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

Over the summer, three cases of the disease were discovered in Michigan deer. The first case was confirmed in May and the last on Aug. 6. In a press release from the Department of Natural Resources sent out when the third case was confirmed, DNR Wildlife Veterinarian Steve Schmidt said the three deer were from the same area and that testing at Michigan State University’s Molecular Ecology Laboratory showed they were related to each other.

The animal develops lesions on the brain after becoming afflicted with CWD. The resulting brain damage impairs the animal’s decision making abilities and eating habits. Eventually deer and any other animal with the disease dies from starvation. Chronic wasting disease is 100 percent fatal. There is no cure or treatment.

“Chronic wasting disease is basically the same thing as mad cow disease, except in deer, elk, and moose,” said Nicholas Boles, a junior at CMU and part of the class group trying to raise awareness of the disease.

According to DNR Deer/Elk/Moose specialist Chad Stewart, it’s hard to tell how much damage the disease can do to the deer population.

“It hasn’t built up enough into the population yet,” he said. “We don’t want it to get to that level.

Although there is no evidence CWD can spread to humans, the Department of Natural Resources in Michigan recommends deer that test positive should not be consumed. Stewart said the disease can be present in the animal for an average of two years, though some survive with the disease for as long as five years.

“Not a lot of people know CWD is out, and you should test it before you eat it,” Rutkowski said.

Rutkowski and the other students in the class group will be volunteering Nov. 8 to help check deer at the DNR Lansing Customer Service Center during hunting season. Rutkowski said they would be working with Jennifer Olson, the DNR public land matters biologist for the southeast region of Michigan. Olson serves with Rutkowski’s father on the Fenner Conservancy Board of Directors in Lansing.

The DNR created a CWD management zone consisting of Clinton, Ingham, and Shiawassee counties. Within these counties is a core zone consisting of nine townships closest to where the infected deer were found. All hunters in the core zone will be required to have their deer tested for CWD.

Although CWD has not been found in or near the Mount Pleasant area, hunters can have their deer checked at Chipp-a-Waters Park at 402 High Street from Nov. 16 to 20.