Investigation details emerge: The case Central Michigan built to fire Jerry Reighard

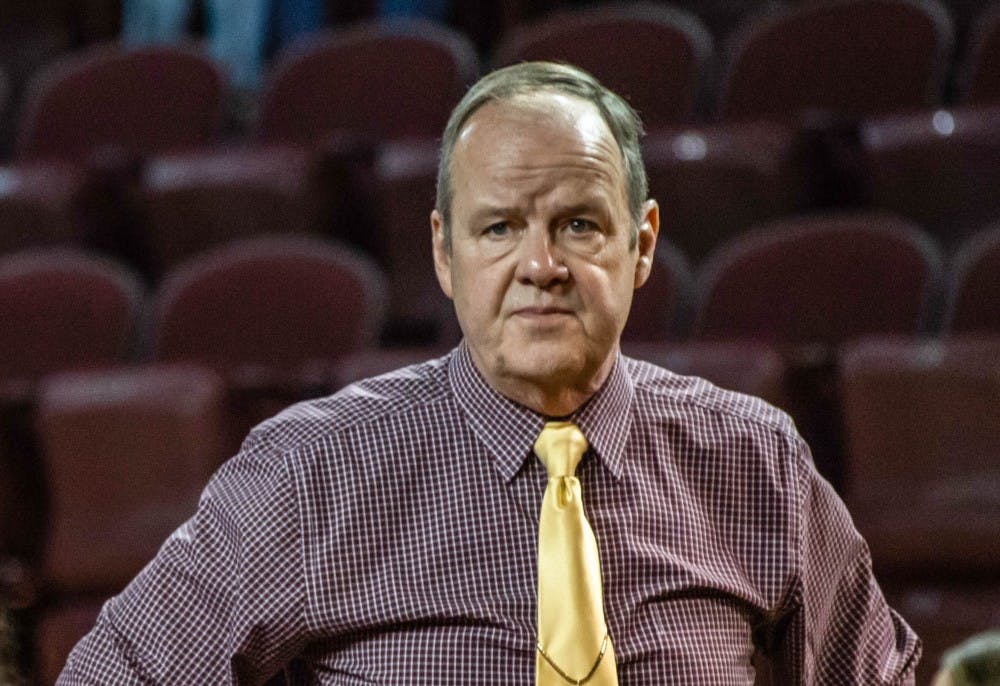

Central Michigan University Gymnastics Head Coach Jerry Reighard watches a gymnast compete during exposition during the CMU vs. Illinois State University meet Jan. 11 at McGuirk Arena.

Jerry Reighard was the leader, mentor and head coach for the Central Michigan gymnastics team dating back to 1984.

He built a legacy of winning.

On April 18, 2019, Reighard's 35-year reign ended. He was fired after a lengthy internal investigation that found the coach encouraged a student-athlete "to provide false information to medical staff related to her fitness to compete."

Dennis Armistead, executive director of Faculty Personnel Services and Scott Hoffman, director of Faculty Employee Relations also found that Reighard had "committed egregious misconduct" by attempting to undermine CMU's mild traumatic brain injury concussion management plan, created a "hostile and contradictory" atmosphere regarding CMU's independent medical model and sports medicine staff, and violated NCAA rules and regulations.

The injury occurred Feb. 15, and Reighard was placed on paid administrative leave Feb. 20 when the investigation began. Reighard did not respond to a request for comment.

Through a Freedom of Information Act request, Central Michigan Life obtained the 121-page report given to Reighard regarding the investigation. The university did not charge a fee to fulfill this request. The university charged Central Michigan Life more than $400 when it previously requested Reighard's personnel records.

Twenty-four people were interviewed in the investigation, which included all current team members, medical and athletic training staff. Reighard was the last to be interviewed.

Interviewing Reighard, concussed gymnast, Linford

Armistead, Hoffman, Cristy Freese, executive associate athletic director and Rachel Blunt, associate athletic director for Institutional Support Services conducted the interviews.

On Feb. 20, assistant coach Cameron Linford submitted a written statement regarding the conversation between Reighard and the injured student-athlete one day prior.

"(Reighard) then said something to the effect that if this type of thing happens in the future that there are certain keywords or phrases that will surely put the medical staff on red alert — phrases like 'I can't remember' or 'I have a headache,'" Linford stated.

Linford was then interviewed by Hoffman and Freese on Feb. 26. He told them the exchange between Reighard and the gymnast took place in his office, and he was there to listen. Linford said the athlete "acted normal" during the meeting, and she was a "team leader" for the Chippewas. Linford didn't explain much to Hoffman and Freese other than claiming some athletes are more likely to "push through injuries" and others would rather hold back.

"Linford noted that (Reighard's) mentality is that CMU student-athletes have to outwork other programs because they don't have as high of a natural talent level," the report stated.

Before speaking to Linford, investigators interviewed the student-athlete on Feb. 22. She was accompanied by her teammate. Both names were redacted in the investigation report.

When the gymnast arrived at the athletic facilities on Feb. 19, she spoke with associate head coach Christine MacDonald, who advised her to discuss the concussion injury with Dr. Noshir Amaria.

After going through the correct protocols, Dr. Amaria diagnosed the athlete with a concussion. Reighard then called the gymnast into Linford's office where he was present. She said that Reighard told her that if she, or any other team member, experiences a concussion in the future she "shouldn't say that she has a headache or that she can't remember something."

The athlete told investigators Reighard essentially wanted her to lie about the concussion, and future concussions, in order to compete.

The student-athlete informed student trainer Kelsey Aldworth of Reighard's statements, and that information was relayed to trainer Kristen Jackson. Those involved that specific situation said they were not shocked by Reighard's comments because he "often minimized other student-athlete injuries" in recent history. The concussed gymnast also told investigators that some of her teammates often worry they will get in trouble by Reighard for reporting injuries or asking to sit out of competitions and practice due to an injury.

MacDonald said Reighard wasn't receptive to student-athletes when they are concerned about doing too much activity in practice. She also told investigators that Reighard occasionally met with gymnasts without anyone else present.

While Linford, the athlete and many others were interviewed in mid-February, Reighard was not spoken with until March 28. He was accompanied by his faculty association representative and a lawyer employed by the Michigan Education Association.

Reighard acknowledged receiving cautions from multiple members of the athletic department throughout his years at CMU. He also noted some of his injury-related conversations with student-athletes in the past came after he was told to change that type of behavior by the medical staff and his supervisor.

"(Reighard) offered the justification for his actions that he had experience and expertise as a coach and that, because of that, his continued behavior in this regard was justified," the investigation report stated.

After Reighard explained his side of the story in terms of what happened in that assistant coach's room on Feb. 19, he began to detail more of the situation.

Reighard said he spoke with Jackson, who informed him there was "likely no way" that the athlete would be cleared to participate against Bowling Green on Feb. 22. He wanted to have a conversation with the gymnasts about "how things work in the real world," so he called her in for a meeting.

During the meeting, Reighard claims to have told the athlete that "words have meaning in the real world" and that using words like "headache" and "I don't remember" are going to issue a predictable response from the medical team. He told investigators that he was trying to explain there are real-world consequences to words used, specifically speaking to the concussion.

Reighard denied telling the gymnast to lie about her concussion.

The longtime coach defended himself on multiple occasions, stating that concussions are "very rare" for a gymnast and that he's had his athletes sit out of competition in the past. However, he acknowledged speaking with student-athletes directly regarding injuries on multiple occasions. He admitted to advising his gymnasts to "engage medical services of a chiropractic or outside medical professional" and to buy personal supplements. He told athletes to meet with outside medical providers, even after he was repeatedly told by the sports medicine staff at CMU to stop that type of behavior.

Reighard also confirmed that he spoke with two gymnasts about permanent medical disqualification, something CMU's policy does not allow him to do.

Gymnasts speak to investigators

Even though concussions were "very rare" in Reighard's opinion, one current gymnast said she's had two since arriving at CMU. The first one happened when she hit her head during the practice of a floor routine.

Reighard was spotting her, which means he was observing nearby. He told investigators that she "barely hit her head." The second concussion occurred when she mistimed her bar dismount. The gymnast told investigators she was nervous to confront Reighard. When she did have the conversation with him, she said Reighard was "done with her."

Reighard also apparently engaged in a conversation with her regarding her weight when she was a freshman. The gymnast said Reighard told her she was too fat. She stated that he told her to say aloud to him, "I'm fat, I'll come back skinnier" before she was allowed to leave for winter break, according to the report.

Another gymnast said Reighard was her spotter at the time of her injury. There was no trainer in the gym at the time. Once she was injured, Reighard told her that he would not help her out of the foam pit. He made her crawl out of the pit alone, while injured. She added that Reighard pushed athletes beyond safety limits.

One of the concussed athlete's teammates had a conversation with her on campus Feb. 20, and the pair spoke over the phone later on. The injured athlete involved in the investigation explained to her teammate that Reighard told her that she shouldn't have told the trainers about her concussion symptoms and that it should be hidden in the future. The teammate expressed concern about the situation in an email to Armistead.

"I was not shocked to hear that (Reighard) said something like that to (the gymnast)," she wrote. "At times (Reighard) is not very receptive to complaints regarding injuries, and I myself have felt very hesitant to voice my concerns to him in the past. In my own experience during my freshman year, I was told by (Reighard) that I needed to push through my shoulder injury and train if I wanted to be concerned for a lineup spot in competition. At times (Reighard) can take on a "win at all costs" type of attitude and it did not shock me that he would recommend that (the gymnast) should be untruthful in future instances in order to compete, as (the gymnast) is a key player on two events."

Another student-athlete said Reighard told her that anytime she has a concussion, they shouldn't explain details to the medical staff. This gymnast said team members are usually fearful of telling trainers or coaches about injuries because Reighard might lash out.

Another gymnast said Linford, an assistant coach, often expressed that he "didn't fully believe her" when she reported her injury symptoms. She said she was forced to compete before fully recovering from injuries as a freshman.

Investigators reported that another gymnast said she doesn't tell trainers and coaches all of her injury symptoms. This student-athlete noted that, in a conversation with CMU trainers, she requested to see a chiropractor due to the recommendation of Reighard. The coach often told students to seek outside medical attention, something that he was previously informed was not allowed.

A gymnast stated there is a culture of "pushing through" injuries within the program. She suffered a concussion during her freshman season with the Chippewas. The team physician and trainer diagnosed her with a concussion, but she was supposed to participate in the upcoming meet. Rather than holding her out due to a diagnosed injury, Reighard had her compete.

She also told investigators that most gymnasts are afraid of reporting injuries because they might "get yelled at," disciplined or taken out of the long-term lineup.

MacDonald, Jackson, Amaria, Wiese open up to investigators

MacDonald, Jackson and Dr. Amaria and Brian Wiese, the director for sports medicine, were four other key members interviewed by CMU's investigative team.

From 1987-91, MacDonald was a student-athlete for CMU's gymnastics program under Reighard. She started as an employee in 1994.

MacDonald told investigators that Jackson, who is the trainer, makes final decisions on whether a student-athlete can compete, and there is no room for questioning her determination. However, she said coaches and trainers often discuss "event-specific considerations relating to injuries," the report stated. MacDonald added that coaches often check to see how athletes feel physically. She said some athletes like to push through injuries, while others do not. MacDonald said she's known of athletes that did not disclose their injuries to trainers.

Jackson stated that Reighard didn't always follow her direction regarding injuries of gymnasts. She believes Reighard acted differently when she was not around by questioning her expertise as a trainer to others in the program.

Reighard broke CMU's Independent Medical Model in late 2018, and Jackson said she knew of it. He also had a number of other injury-related conversations that went against policy.

When speaking with investigators, Reighard was asked directly if he violated the policies, even after being told to stop. He admitted to doing so but explained to them it was because he was a head coach for 35 years.

Dr. Amaria, during his time with investigators, noted a long history of concerns with Reighard violating the policies set in place by CMU. These violations included sending student-athletes to physical therapy without involving the medical staff, speaking with student-athletes directly about injuries and advising them on personal medical treatment.

"Dr. Amaria noted that he was stunned and shocked that any coach would do what (Reighard) was alleged to have done," the investigation details.

Wiese told investigators Reighard had a history of "fat-shaming" gymnasts, disregarding their injuries and that his coaching tactics were harmful to the mental health of his athletes.

Following all interviews, the investigative team concluded that Reighard violated CMU's Independent Medical Model regarding the original complaint made by the concussed student-athlete.

"No coach should have any influence, direction, or implementation of health care actions or plans for student-athletes," the report stated.

"In short, there seems to be no reaching this particular coach about the link between student-athlete safety and the need for an independent medical authority to have exclusive dominion over student-athlete health and well-being," the report concluded.

What's next?

Now that Reighard has been fired for "egregious misconduct," as noted in CMU Athletics' press release, Athletic Director Michael Alford will conduct a national search for a new gymnastics coach.

Alford also said CMU has already been in contact with the NCAA, as the findings in the report could lead to an NCAA violation. Alford said he will fully cooperate in self-reporting each matter.

“Our student-athletes and their families trust us to protect our students,” Alford said in a press release. “We will not tolerate a callous disregard of safety. We will not tolerate actions that put students in the way of significant and even life-threatening injuries.”