From telehealth to training: CMU Institute tackles rural health gaps

From maternal health deserts to internet dead zones, rural communities across Michigan face a web of challenges that threaten health and quality of life.

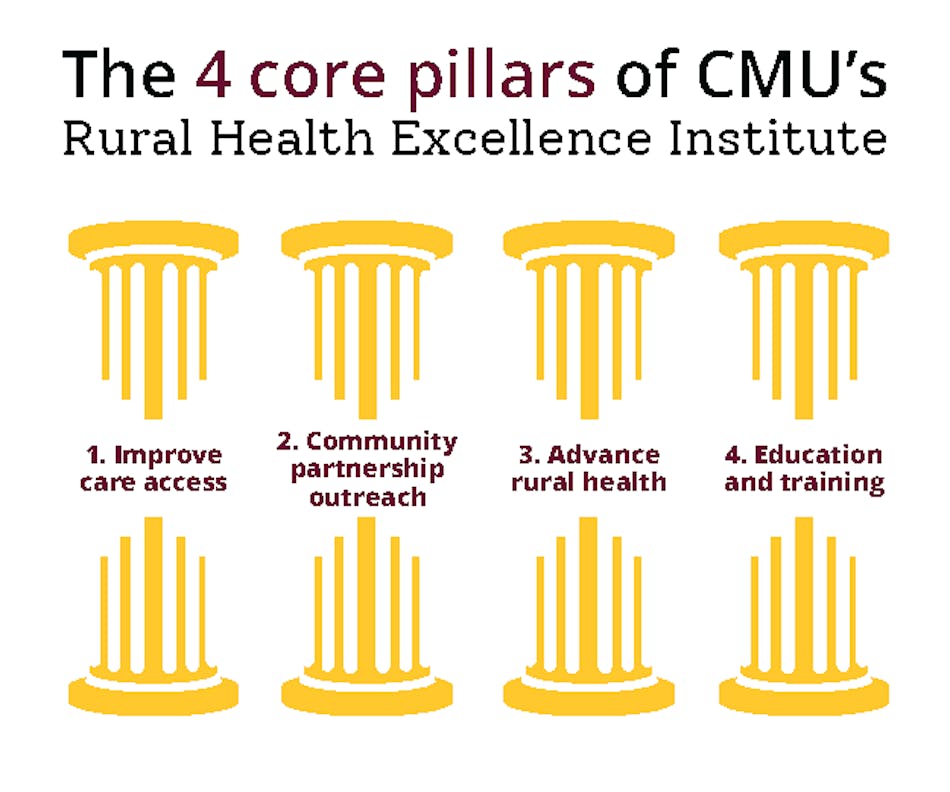

The Central Michigan University Rural Health Excellence Institute (RHEI) is working to change that through its four pillars: improving care access, building community partnerships, advancing rural health innovation and expanding education and training.

“Sometimes one of those big challenges is just the capacity to get resources,” Alison Arnold, executive director of RHEI said. “Whether it’s getting their fair share of medical providers … or their fair share of funding. ... That’s something we recognize that we could maybe be an institute to team up with and work side by side with leaders in rural communities across Michigan.”

Arnold noted that although 94% to 95% of Michigan’s geography is rural, only about 20% of the state’s population lives there. That imbalance means small communities often struggle to attract providers and investment.

“If you’ve seen one rural community, you’ve only seen one rural community, because they’re all so different,” Arnold said.

Courtesy of Ben Westerhof

Pillar One: Improve Care Access

Access to basic health services remains a pressing issue in Isabella County.

According to MyMichigan Health, there are about 2,040 patients for every primary care provider in Isabella County, which is worse than the Michigan average.

“There’s what we call maternal health deserts in a lot of our rural communities because there’s no OB-GYN in that community,” Arnold said. “Many of our hospitals are now closing their birthing units … so we’re trying to team up with hospitals and rural physicians and providers to build capacity.”

The institute is also working on non-emergency medical transportation research.

“Maybe I need a cancer treatment, maybe I need to go to dialysis, maybe I need to go get some blood work done,” Arnold said. “There are some communities where people just can’t even get to their doctor’s appointments. We’re doing some research right now on how we might be able to support the building up of more services to provide transportation for medical needs in rural communities.”

Pillar Two: Community Partnerships

Many projects emerge directly from residents. Arnold cited a northern Michigan group studying health disparities in Tawas, where researchers found an eight-year life expectancy gap compared to people living in Traverse City. This is because citizens in the Traverse area have access to the emergency room and physicians.

“They got pretty riled up and they’re like, 'We’re going to do something about this,'” Arnold said. “They worked with us — CMU helped them get their IRB to do their research … and that’s how they learned that we can do something about this. This is a real genuine need.”

An IRB stands for Institutional Review Board, which is an independent committee that serves as a safeguard for people who participate in research studies. The institute also partners with many hospitals, physicians mental health institutes to reach all areas of medical need.

Pillar Three: Advancing Rural Health Innovation

The institute has also become a partner in research pilots, including a project testing drone delivery of lab samples to cut down delays.

“It’s pretty exciting to think about how might that use of different kinds of mobilities speed up the access to care,” Arnold said. "An almost-$700,000 grant from the State of Michigan gave Traverse Connect and several other organizations the ability to begin testing the use of unmanned aircraft systems to deliver medical supplies."

Telehealth is another innovation that can break down barriers, though not without limitations. Telehealth is the practice of providing health care services and information remotely using devices such as computers, smartphones or tablets. Through secure texting, video conversations, phone calls, or even remote monitoring devices, patients can communicate with medical experts without always needing to travel to their doctor's office.

“Telehealth could be a phone call, but ultimately the ideal is like what we’re doing,” Arnold said, gesturing to the virtual interview format. “But many rural communities don’t have access to broadband… so communities that lack broadband, a lot of times they’re where the maternal health deserts are. It’s a double burden.”

Broadband is high-speed internet access that is always on and much faster than older dial-up connections. It’s what makes streaming, video calls, online learning and Telehealth possible.

Pillar Four: Education and Training

Arnold said student involvement is central. With Central Michigan University in its backyard, the institute is tapping into a pool of future doctors, nurses, social workers and public health leaders who bring fresh energy and ideas to rural health challenges.

The institute also has interns and is open "when some of our medical faculty and students have come to us and said, I’m interested in this issue in a rural community," Arnold said.

“There’s no substitute for just getting out into the field and just getting involved,” she said. “Do a clinical clerkship, do an internship, reach out. Whatever you’re interested in — how does that play out in a small town or a rural community? There’s just no substitute for that.”

Looking ahead, Arnold hopes to see CMU expand specialized programs in RHEI for medical, public health and allied health education.

“I think there’s really an opportunity that we can help play to provide not just the lens, but the applied learning to CMU students who are looking for that rural experience,” she said.

One of those CMU medical students is Grace Greig.

Grace Grieg is a CMU medical student. Courtesy of Grace Grieg.

She worked with Arnold for the last few years to support numerous aspects of the PRiSMM suicide prevention project at CMU. PRiSMM is Preventing Suicide in Michigan Men. She has been part of community outreach, helped to generate data for community leaders to review and participated in faculty-student research endeavors associated with her involvement in these areas.

“I really just like to do the research for them,” she explained. “If they need me to find statistics for the counties that we cover in Michigan, that’s what I usually do. Sometimes I put them together in a PowerPoint for when we all get together.”

She emphasized that national data doesn’t always reflect rural Michigan’s reality.

"The national data says, let’s target men in their 30's to 50's because that’s who are committing suicide the most," Greig said. "And that does fall with our statistics too, but we’re also noticing we have other areas that we can focus on more than just what the national data provides.”

Greig’s motivation comes from personal experience and a broader concern for her future profession.

“I really care about the stigma behind physicians and medical students getting help because we also have the highest suicide rate in our profession,” she said.

For her, sharing her own story is part of changing the culture.

“I just talk about my mental health and I talk about all the things that I went through because I hope that if at least one person hears it and feels better about themselves — that’s my goal,” Greig said. “I don’t really care if people think I’m weird. I just care that somebody feels seen.”

If you or someone you know is in emotional distress or a suicidal crisis, you can reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline by calling or texting 988.