CMU has wide gender gap among highest-paid faculty, full professor pool

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct a miss-attributed quote.

If you look for women earning prominent wages as faculty at Central Michigan University, you'll have a hard time finding them.

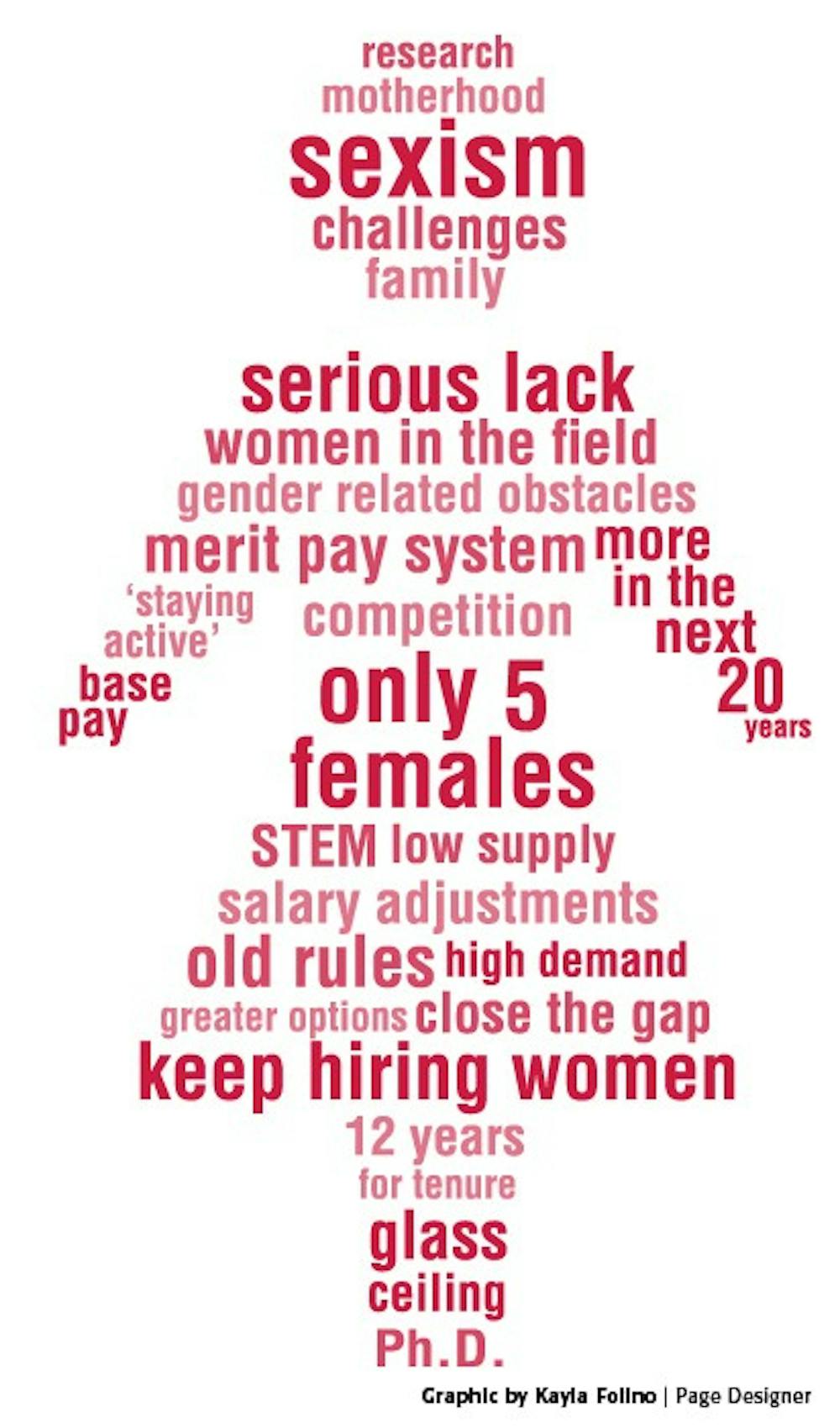

Only 28.9 percent of full professors at CMU are female, and out of the top 50 highest-paid faculty members – including chairs for departments – only five are female.

Compounding the gender gap, university officials have cited specific challenges in attracting female instructors and potential faculty to teach subjects like science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).

“Across the colleges and across the departments, there are different disciplines commanding different salaries,” said Joshua Smith, president of the Faculty Association and a philosophy professor. “If you couple that with the long-standing problem that different disciplines have a hard time attracting women, like accounting or chemistry or philosophy, (higher education is) sort of the leftover one that has a serious lack of representation of women."

Specific challenges for CMU and other universities include competition for qualified female STEM instructors, as well as competition with large companies and firms for women with STEM backgrounds.

“(CMU) has to make the position competitive,” Smith said. “(The faculty member) could go to another university or to a firm and make a lot more money.”

Where are the women?

Despite CMU's lack of high-earning female faculty, Robert Roe, executive director for Institutional Research and Planning, said the number of women graduating with doctoral degrees is increasing nationally.

Backing his assertion, data collected by websites like insidehighered.com show that more women are able to take higher positions in non-STEM fields.

However, the number of STEM graduates moving into teaching positions is low, said Ann Miller, director of faculty employment and compensation for Faculty Personnel Services.

Miller said women in STEM fields are generally a smaller part of the workplace population.

Women with STEM degrees do have a multitude of high-earning career options when they graduate with doctoral degrees. Higher-education institutions often lose out on catching these and other non-STEM women as employees.

“When (women) are in a pool and they rise to top candidate, they often have other offers because they’re in other pools, too,” she said. “That’s what CMU is competing against, those multiple offers (from) institutions much larger than ours.”

Why professors get paid the way they do

Challenges in attracting prominent women helps to explain the low supply of female professors, but it fails to explain exactly why so few female faculty earn high wages at CMU.

Smith said it has more to do with the choices of women in these fields, as well as the length of time it takes to reach tenure as a faculty member.

There are four levels of CMU professors, which includes instructor, assistant professor, associate professor and full professor, Smith said. Each level has its own base pay.

From there, faculty members have a built-in 1.5 percent salary increase, plus $835 allocated to them in their 2013-14 contract. The percentage increases give senior faculty members a higher-pay wage than those with lower starting salaries.

After a faculty member has been around for a certain amount of time, they can become a full professor and apply for salary adjustments every four years. Smith said professors can apply for a higher wage using a merit pay system.

“As long as they’re staying active, then they can apply for another professor salary adjustment (and) they can earn themselves a raise,” he said. “It’s rewarding those who stay active, those who are clearly on top of their field and share their knowledge with students.”

Staying active, Smith said, includes doing research in the field, writing essays for publication and attending conferences to help advance their students’ experiences in the classroom.

This can also vary a professor's class loads, sometimes allowing them to teach only one or two classes as a trade for spending more time on research.

Roe said it's up to each faculty member to decide if they want to stay active to receive merit pay, explaining "it's a choice to be promoted."

Unintended institutional sexism

However, that "choice to be promoted" can come at a cost for the female workforce at CMU.

Doing the kind of work that necessitates merit pay, such as research, sometimes runs counter to personal goals, like getting married and raising children.

This forces female professors to make choices their male counterparts never have to.

“Historically, that’s been a bigger problem for women than for men,” Smith said. “If a woman decides to start a family and she’s lucky enough to have a supportive spouse who can share the load – let me put it this way: it’s difficult for a family not to get in the way of research.”

Roe said it takes about 12 years to become a full professor. The faculty members in the top 50 highest-paid positions have been here an average of 30 years, with the longest tenure at 45 years and the shortest at four years.

Chairpersons of departments also make more money than their other faculty counterparts, Roe said. However, only seven of the 36 department chairs are in the top 50 highest-paid bracket.

Fixing the gender gap

University officials have recognize the gender gap on their hands and have been hiring women at a higher rate in the past 12 years, Roe said.

“There were fewer Ph.D.’s granted to females at the time when many of the full professors were hired, an average of more than 12 years ago, and often more than 20 years ago,” he said, “which is reflected in the gap in proportion of female full professors.”

The gender gap is closing as assistant and associate professors are promoted over the years, Roe said. Associate professors – those who were hired between six to 12 years ago – are close to becoming full professors: 44.9 percent of them being female and 55.1 percent being male.

Assistant professors, including new hires and those hired up to five years ago, have an even closer ratio of women to men, with 49.3 percent females and 50.7 percent males.

“Among assistant professors who were hired an average of less than five years ago, the proportion of females to males is almost identical,” Roe said. “It’s important to have an environment that supports everyone.”

As full professors retire and associate professors are promoted, the gap will close even faster, Roe said.

However, that process might be slower than one would hope; one that depends heavily on what professors are going to retire.

Optimistic about female professors staying at CMU and increased recruiting efforts, Roe believes the next two decades will see higher numbers of women with top wages.

"The gap will continue to lessen," he said. "You're already seeing a significant change at the associate level."

Meet the five women in the Top 50

1. Thomas Weirich is the highest-paid faculty member on campus. He is a member of the accounting department. Weirich has been at CMU since 1970 and makes $183,379 annually.

2. J. Holton Wilson is a member of the marketing and hospitality services department. He has been a faculty member since 1979. Wilson has an annual salary of $167,844.

3. Philip Kintzele is an accounting professor at CMU. He has been a faculty member since 1981 and has an annual salary of $164,582.

4. William Cron has been a faculty member since 1982, and is a professor in the accounting department. He makes $163,315.

5. Roger Hayen rounds out the Top Five highest-paid faculty members on CMU's campus. He is a professor in the business department and has been a faculty member since 1987. Hayen has an annual salary of $162,507.