Sentenced to Debt: Tuition increases a result of state defunding, rising costs

In 2001, "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone" broke Box Office records, millions of viewers watched Britney Spears dance with a python at the MTV's Music Video Awards, and undergraduate tuition at Central Michigan University was $276 cheaper per credit hour.

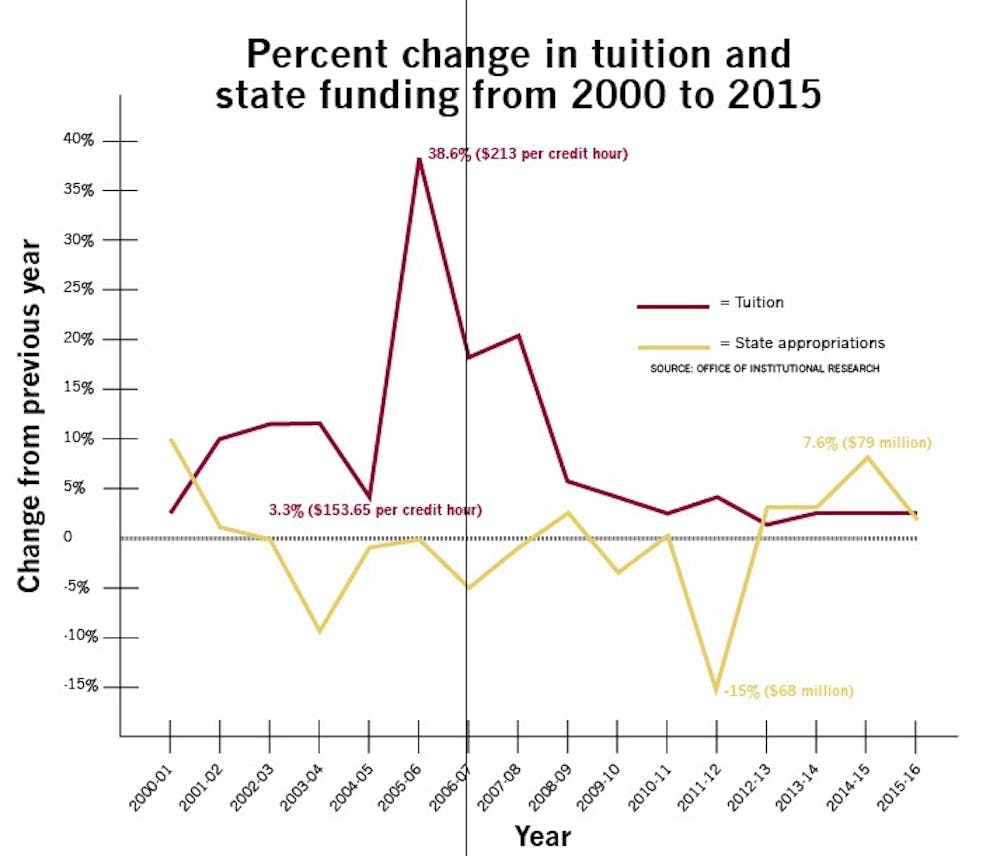

In 15 years, undergraduate tuition has increased by 265 percent.

If you are an 18-year-old incoming freshman, each credit hour is $300 more expensive at CMU than it was when you were born.

Gov. Rick Snyder's 15 percent cut to funding for higher education in 2011 significantly impacted the cost of attending a state university, placing the burden on student dollars to feed growing budgetary needs.

"When we're building the budget, we have to look at the revenue side and the expense side," said Barrie Wilkes, vice president of finance and administrative services. "What we do is come up with a tuition increase number that will balance both sides of that equation. If we end up getting a reinvestment from the state, that means the tuition increase will be lower, because we need less money to balance the investment side of the budget."

Tuition is responsible for more of CMU’s budget than ever before. Student dollars comprises 57.7 percent of the operating budget this State appropriations funded only 16 percent of the budget.

Wilkes said if CMU received the same amount of appropriations as in 2001, adjusted for inflation, it would reduce tuition by $100 per credit hour. That year, tuition accounted for 36 percent of CMU’s revenue.

State budget reductions happened predominantly from 2002-03 through 2011-12, causing Michigan universities to substantially increase tuition.

“In the short-term, honestly I wish I could tell you that tuition increases are going to stop,” said University President George Ross. “Unless the state does more than partially restore a cut they made six years ago, it's going to be tough to (end) that.”

This is bad news for students like Tara Kozlowski, who said she has a difficult time covering the cost of tuition every year.

"I just feel like they made it hard to continue education if they make (tuition) so expensive, because not everyone can afford to go, even if they want to," the Zeeland junior said.

In 2001, the average annual undergraduate tuition for residents at Michigan's 15 public universities was $4,928 per semester, according to a report compiled by the Senate Fiscal Agency. In 2014, the average annual resident undergraduate tuition was $11,142, a 126 percent increase compared to 2001.

Higher education funding has been partially restored since the 15 percent cut five years ago. However, there is a $400 million difference from what the state dedicated to Michigan’s universities in 2001 and today.

“I've looked the governor dead in the eye and said ‘If you get us back to funding levels in 1999, I'd cut tuition about $100 per credit hour right now,’” Ross said. “(Raising tuition) is not something we do lightly. We're a state university that receives about 16 percent of it’s funding from the state. We're quickly becoming private.”

Spending has almost doubled in 15 years, from $261.4 million in the 2001-02 academic year to $483.2 million in 2015-16.

CMU’s most expensive financial commitments are to employee compensation and funding non-revenue generating service centers, both of which are dependent on enrollment. Total compensation has increased by 163 percent since the 2001-02 academic year, while service center expenses have more than doubled.

Covering costs was easier in the past, Wilkes explained, because universities knew the majority of funding would come from the state. Tuition was “fringe money." He agreed with Ross, comparing CMU's funding model to a private institution.

“We understand that at $395 a credit hour, we are pricing students out of an education and that is not a good thing,” Wilkes said.

HISTORICAL POLITICS

Not all state universities receive the same amount of state funds. Compared to other universities, CMU must do more with less.

CMU will receive $80.8 million in state appropriations this year. Last year it received the fifth-highest amount of appropriations, but ranked 10th among Michigan’s universities in the amount of funding it received per student — about $3,787.

According to information on Michigan’s public universities compiled by the Senate Fiscal Agency, funding for the state’s 15 public universities ranged from $2,830 to $8,414 per student last year. Wayne State University received the most per student and Lake Superior State University received the least.

Despite having 300 more students than Western Michigan University, CMU received $1,000 less per student. The university receives $20 million less overall in state-appropriated funds.

Ross and Wilkes said there is little CMU lobbyists in Lansing can do to resolve the issue quickly.

“Per student funding from the state is purely historical and political,” Wilkes said. “The newer schools are receiving some of the lowest (funding); part of it is a simple math problem where what the state has (said) ‘here is your $90 million CMU,’ they don't care if we gained 5,000 students or lost 5,000 students. If we lose 5,000, our per student funding just went way up, and vice versa.”

Ross said this penalizes growth, because appropriations aren’t adjusted by enrollment.

“For years, CMU and some of the other schools that are receiving lower amounts of funding have been lobbying for more equitable per student funding,” Wilkes said. “When (Ross) made his presentation to the Senate (last year), he lobbied hard for per student funding. Then you heard the president of Wayne State say that per student funding would be a bad thing for Wayne State. Everybody has their story.”

Snyder enacted additional academic performance-based funding, which is allocated on the number of students receiving Pell Grants and other factors. CMU received $2.3 million this year from performance funding, but that is a small part of the overall appropriation.

“The challenge is, if we went back to per student funding you would bankrupt some universities who couldn't take a cut,” Wilkes said. “So how do we address the huge inequity you have without putting some schools out of business?”

Ross said he does not advocate taking monies away from universities to equate them on a per student basis, but does support per student funding.

“I believe it’s the responsibility of the State of Michigan to have the dollars follow (undergraduate) students,” he said. “I just don't think that's fair (the way it is now).”

LOBBYING AND LEGISLATORS

Representatives of CMU lobby legislators in Lansing throughout the year. Ross said they try to explain the value of higher education and need for more state support.

Vice President of Development and External Relations Kathy Wilbur, Director of Government Relations Toby Roth and Ross are responsible for working with elected officials to improve annual state higher education funding for CMU.

Wilbur works with state legislators, identifying other areas of the budget able to provide funds to specific CMU programs and tracking pieces of legislation that could have an impact on CMU programs. She also works as a liaison to introduce CMU personnel to Lansing policy-makers.

Wilbur was helpful in securing a $30 million capital allocation for the new Biosciences Building. The allocation was signed by Governor Snyder in June 2012.

Michigan House Speaker Kevin Cotter was unavailable for an interview by the time of this publication, however he sent an statement to Central Michigan Life via email.

“Kathy Wilbur and Toby Roth do a terrific job representing Central Michigan University and promoting all the great things the students at this school achieve," Cotter said in the statement. "They've played a significant role in making the case for CMU to receive funding increases from the state for each of the past four years. I've always been a big fan and a proud alumnus of CMU, and I look forward to working with Kathy and Toby in the future to ensure strong support for the school’s academics and higher education in general.”

Roth works with the Michigan Congressional Delegation to raise the profile of CMU in Washington D.C. He said there has been a growing recognition that investment in education is critical if Michigan is to stay competitive with other states.

“(Reception from legislators) has been positive overall,” Ross said. “I think it's positive because tuition increases have been low. I've shepherded six since I've been here. The total increase has been 13 percent in six years. That has had a very positive reception from Lansing. They know we are trying to control costs at CMU.”

CMU’s 11.2 percent cumulative five-year tuition increase is the lowest among Michigan public universities. Wayne State is the highest, increasing tuition 26.9 percent since Snyder’s biggest cut in 2011.

CMU ranked fourth among Michigan’s 15 public universities in cost per credit hour last year, behind Michigan State University, which charges $440 per credit hour.

“I think the state, (and) the country, needs to invest in education,” Wilkes said. “A lot of people talk about how important education is and then cut budgets. I understand the people in Lansing — when the economy is bad — don't have any easy decisions.”

SOLUTIONS

There are a few things CMU can do to take the burden off students.

One of those is diversifying revenue sources, Wilkes explained. The primary diversification strategy CMU is focused on is fundraising and scholarships.

Another area is securing more funded research projects. Indirect cost rates negotiated with the Federal Government gives a percentage to apply toward overhead costs. These grants don't make any money, but help cover costs associated with research.

The addition of the College of Medicine, CMU Research Center and the Biosciences Building brings access to research grant funding that wouldn't have been available before. These have also been major areas of investment.

Construction on the Biosciences Building is estimated to cost $95 million and CMU has dedicated $49.2 million in subsidies to the College of Medicine since the 2010-11 fiscal year.

Wilkes acknowledged that some are critical of the expansion being paid for primarily by undergraduate students who will not benefit from these projects.

“Any investment that we make that comes out of the general fund, 57 percent of it is tuition,” Wilkes said.“So if we're increasing the athletics subsidy, a lot of it is coming from the students. So the Biosciences Building, the state gave us $30 million. We're looking at an addition for Grawn Hall and told the dean if he raises $5 million we will contribute $5 million. Is somebody in (the College of Education) contributing to the expansion of Grawn Hall? Yes, just like the people in the College of Business Administration contributed to the new education building, or new music building and so on.”

Wilkes said there is an ongoing fundraiser campaign for CMED with a goal of $25 million.

While CMU's budgetary needs continue to grow and state support diminishes, Ross said his priority is to keep costs low for students.

“I do think about families. Man, I struggle with that every year when it comes to tuition time,” he said. “I struggled with it again last year, but we were the lowest in the state. I've had people pushing back to me saying that we could have increased higher. Then what? I'm proud that we have increased the student financial aid in the time I've been president.”