Where your tuition dollars are going

University continues to rely on tuition dollars as state aid decreases

Student tuition dollars make up more than half of the $492 million that fuels Central Michigan University’s budget.

That is unlikely to change anytime soon.

With a 3.4 percent projected partial “restoration” of money allocated to CMU from the State of Michigan, the almost half a billion-dollar operating budget increased by $9 million from last year. Tuition increased $10 per credit hour from last year, totaling to $405 per credit hour for undergraduates. For grad students, tuition increased 3.9 percent to $548 per credit hour.

The operating budget, which funds all university operations, is drafted by the Budget Priorities Committee. This budget was approved at the June 28Board of Trustees meeting. According to administrators, the operating budget process is designed to link “strategic planning with operational planning and provide a perspective of the operating needs of the university.” The annual planning process takes into account projections for enrollment, tuition, other revenue and expenditures for that fiscal year, and determines how much money will be distributed to each college and service center.

The committee is holding an open forum at 3:30 p.m. Oct. 26 in the Charles V. Park Library Auditorium to get input from the CMU community for designing next year’s budget.

The budget is available for anyone to read on CMU’s website, but students aren’t expected to understand what it means — even though every year their dollars play a bigger role in the operation of the university.

Tuition, financial aid increase

Students taking 15 credit hours both semesters will pay $12,150 to the operating budget if they receive no scholarships or financial aid. Conversely, almost $49 million of this year’s budget is “paid back” to the student body through scholarships and financial aid. This aid helped offset the cost for 92 percent of incoming freshmen who receive some form of financial aid or scholarship — from the university and private donors — to attend the university.

Financial aid in this budget increased $2.7 million, which, in total, makes up 9.7 percent of total budgeted expenditures. Financial Aid has increased 5.9 percent from 2015-16. Since President George Ross took office in 2009-10, financial aid has increased by $21 million.

Donor funds toward scholarships are not reflected in the budget.

Besides adding dollars for financial aid, the budget is relatively similar to last year, said Joe Garrison, director of financial planning and budgets.

The $95 million construction cost of the Bioscience Building was not part of the operating budget. Construction was covered by $45 million in bonds, $30 million in state funding and $20 million in university reserves and gifts. About $2 million, however, was included in this year’s budget for the upkeep and utilities for when classes will be held there in January.

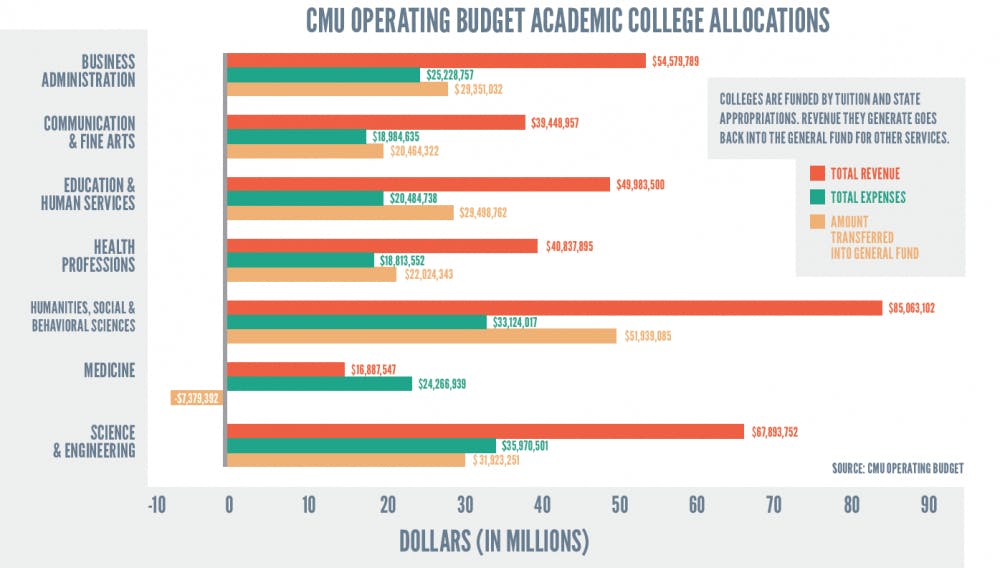

Revenue inconsistent between colleges

Unlike the other six academic colleges, the College of Medicine isn’t bringing in revenue to the Operating Budget. It is the only academic center that isn’t assessed a “tax” to fund centralized services. Instead, this year it will be subsidized $7.3 million by the university to cover its costs.

This year the College of Medicine will be subsidized $2.6 million by the university to cover costs. CMED brings in the lowest revenue at $16.8 million. CMED clinical operations also are subsidized a separate $892,574.

“The projections I’ve seen from the College of Medicine were still projecting a deficit, needing university subsidy, 10 years out,” said vice president of finance and administrative services. “Once they become more active in research, and develop some additional revenue streams, perhaps (that will change).”

According to the budget, “The subsidy is necessary to assure the continued provision of essential clinical, campus health education and other related services to CMU students and the university community.”

When new initiatives for funding programs are requested, Ray Christie, senior vice provost of academic administration, said there is more to consider than just the cost.

“If there is a new initiative request for a program, it doesn’t always need to be low cost to succeed,” Christie said. “We need to look at whether it will have a student impact and what kind of impact it will have on the state we serve.”

The most credit hours, tuition dollars and revenue is brought in by the College of Humanities, Social and Behavioral Sciences. CHSBS also is allocated the most state appropriations, and is assessed the highest amount at $51.9 million. Excluding CMED, the College of Communication and Fine Arts brings in the least credit hours, tuition funds, revenue, and is assessed the lowest amount at $20.5 million.

“CHSBS and CCFA enrollment tend to be more directly affected by the size of the entering class because they offer a lot of the University Program courses that are required,” Christie said.

Covering costs:

Academic colleges and centralized Service Centers receive money from the general fund because they align with CMU’s mission and vision of the institution of instruction and research, Garrison said. There are, however, institutions funded by the operating budget’s general fund that don’t reflect instruction and research and are not self-sustaining.

These Subsidized Auxiliary Centers are considered “something CMU values,” Garrison said.

“The big key of that subsidized piece is it means they are getting some funding from the general fund,” Garrison said. “(Subsidized Auxiliary Centers) are reliant — it could be a small or large extent — on some general fund dollars.”

Athletics is the largest subsidized center, receiving $22.4 million — which is almost double any other subsidy received by a Subsidized Auxiliary Center. Computing support, public broadcasting, telecommunications, CMED clinical operations, university recreation, and events and conference services make up the other centers budgeted to receive subsidies. Money listed in Athletics’ budget includes scholarships for athletes, which was also included in the $48.8 million in financial aid provided to students.

Wilkes said he realizes the cause of debate about the amount of spending on Athletics, but he sees it as a valuable thing at CMU.

“I think Athletics brings a lot to college life,” Wilkes said. “It can bring a lot of publicity, when you think about the Oklahoma State game and how that play was all over the world — so it brings value. The question is what is the balance and how much should we spend on athletics? It’s a good question and people have been debating that for decades.”

Things like UREC and Athletics aren’t instruction-based or research activities, causing them to fall in the non-general fund. They generate some revenue, but not enough to cover all expenses, Garrison said.

As the makeup of the student body changes, so do their needs and ideas of what services CMU should be providing them. The idea of “traditional” college students attending CMU right out of high school is no longer the norm, Wilkes said. That has forced the university to create a plan on how to best accommodate its students.

“We have been working with a consultant looking at developing a Student Life Master Plan,” Wilkes said. “What we’re looking at is what do we need for residence halls, apartments, dining options — residential restaurants and (other food vendors on campus) — and student recreation.”

At the end of each academic year, students await the Board of Trustees decision on tuition rates. Most expect an increase but hope for a decrease.

Ray Christie, senior vice provost of academic administration, doesn’t see a tuition reduction as a likely possibility.

“I would love to see a day when the State of Michigan brings its investment in higher education back to what it was 10 to 20 years ago,” he said. “Short of that happening, I don’t see a day when there won’t be at least some modest tuition increase.”

Because of the state’s delay in finalizing its budget, the governor and Senate’s recommendation for state appropriations — $4.2 million — was the figure used to configure the 2016-17 Operating Budget. The appropriations could change before October, but the State’s budget approved a partial restoration of 3.4 percent, or $2.8 million, rather than the 5.2 percent ($4.2 million) that was part of Gov. Rick Snyder’s executive recommendation that was used to configure the Operating Budget.

“Unless the university received substantially more from the state or outside dollars, I don’t see us being able to reduce our tuition,” said Barrie Wilkes, vice president of finance and administrative services.

Even though appropriations make up 17 percent of the budget, they are still an important piece of funding university operations.

“We actually use appropriations to smooth out some of the ups and downs from enrollment,” said Joe Garrison, director of financial planning and budgets. “We wanted to find a fair mechanism that rewarded (growing programs).”

Each of the seven academic colleges are mostly funded by tuition based on how many credit hours students enrolled for in their respective colleges. This relies heavily on enrollment and can cause “ups and downs” like Garrision said. To help even out fluctuating enrollment, state appropriations are allocated to each college based on a three-year average of the number of credit hours in their colleges.

“I see it more like enrollment can fluctuate here, but this is kind of like more of a steadying stream of revenue,” Garrison said. “Although if the state cuts it, that’s a different thing altogether.”

The state’s fiscal year starts Oct. 1. CMU’s fiscal year begins July 1. The discrepancy between the two schedules can cause issues with budget planning.

“This year we went into the Board of Trustees meeting with the budget before we knew what a final (appropriation) would be,” Garrison said. “We know going into the year that we’re not going to have all of the appropriation funds we thought we might have.”

When it comes to making decisions about where a big chunk of the operating budget money goes, the deans of each college hold most of the decision-making power in which programs to support.

The operating budget model is designed so tuition dollars, money from state appropriations and course fees are funneled to CMU’s seven academic colleges. Depending on precedent and need, a set amount is taken back by the university and added to the general fund. That money is used in part to help fund the university’s 15 service centers, which include widely-used resources on campus such as the library and human resources. That money also supports other costs such as athletics, residence and dining halls, financial aid and payment to faculty, staff and administrators.

CMU’s budget model is complicated to follow, but Joseph Garrison, director of financial planning and budgets, believes it is effective. The university uses a Responsibility Center Management model, he said, which is only shared by one other university in the state — The University of Michigan. The model leaves most decisions to the dean of each college. They know more about their specific college than someone who is not directly in the college.

“If you have to go to one centralized office and get a question answered for everything, imagine how much longer things would take,” Garrison said.

In turn, deans have the added responsibility of having a clear understanding of the budget and how to best use the funds received.

While deans are free to focus on their colleges, what’s good for the entire university must also be part of the budget conversation.

“On the negative side (of the RCM budget model), I think it can have a tendency to make folks live in a silo because they’re making decisions that are best for them,” said Barrie Wilkes, vice president of finance and administrative services. “But we also have to make sure they are making decisions that are best for the university as a whole.”

When departments have unequal enrollment compared to others in the same college, it causes an imbalance in revenue because of the direct tie to tuition dollars. The amount of money it takes to offer a class is not always equal. That means higher revenue departments foot the bill of the entire college more heavily, supplementing costlier departments within the same college that don’t support themselves.

“If the dean sees that biology is booming, for example, they can allocate more resources in their college once the operating assessment is fulfilled,” Garrison said. “They can still make some of those decisions as to which programs should be getting more of the resources within their own college.”

General education and University Program courses tend to be less costly because of high enrollment and the less expensive lecture hall-style format. This contrasts with small courses of 12 to 15 people, or lab based courses which typically cost more, Garrison said.

“A lot of the centralized services are funded from some of the larger classes,” he said.

Service Centers are the main centralized expenditure that receive assessment funding from colleges.

“(President Ross) reminds us frequently, the first priority is student success,” Wilkes said. “Everything we need to do needs to be furthering student success. Most of what we do is heavily subsidized by student tuition. I want to be sure that it’s something that is benefitting a student because you’re paying for it.”

Scholarships, financial aid and the library are among the Service Centers that receive funding that most directly impact students. “I don’t want to have things that might be a benefit to a group or community,” Wilkes said. “If they aren’t benefitting students we look really hard at why we’re doing it.”

The only increases Service Centers receive in annual funding comes from a turnover in staff or an approved funding request.

“(Until) this fiscal year, 25 years ago was the last time service centers received any across the board increase in funding for supplies and equipment,” Garrison said. “They’ve remained constant even though inflation goes up every year.”

If turnover in staff results in a Service Center employee with a lower salary than the person they preceded, the center gets to keep the difference and can allocate it, Garrison said. On the flip side, if someone filling a position earns a higher salary than who they replaced, that comes out of their budget.

“If for some reason, we had a great candidate but we didn’t have the budget funds for it, I could go to my vice president and ask if they could reallocate some resources to hire the new person,” Garrison said. “It’s just a matter of if you’re willing to give up resources or give up someone who is a star candidate.”

Similar to when reallocations are carried out in colleges, reallocations in Service Centers are decided internally and don’t affect the bottom line, said Steven Johnson, vice president of enrollment and student services.

“Last year the financial aid computers were five years old, so we replaced them,” Johnson said. “But I recovered that from the savings we gained from another area (in the Service Center), so it didn’t affect the bottom line, it was just reallocation.”