Pay to Play: Graduate transfer football players accept scholarships, bend NCAA rules to attend university without intention to graduate

Photo illustration of Shane Morris and Thomas Rawls, CMU's most prolific graduate transfer football players.

In one of Central Michigan football’s all-time greatest comebacks, quarterback Shane Morris threw a game-winning, 77-yard touchdown pass with two minutes remaining in the fourth quarter. On a rainy, cold Wednesday night, the Chippewas beat arch-rival Western Michigan, 35-28 in Kalamazoo as ESPN broadcast the game nationwide.

Head coach John Bonamego was so pleased with the signature win, his wife posted a photo of him snuggling with the Victory Cannon trophy as he laid in bed after the game.

Down by 14 points at the half, Morris rallied the offense. Morris rushed for a touchdown, threw a touchdown pass to wide receiver Eric Cooper that tied the game and then fired the game-winner to wide receiver Corey Willis. Throwing his arms into the air, running down the field to celebrate with his teammates, Morris became an instant hero at CMU.

It would be his greatest achievement as a Chippewa. It also stands in stark contrast to his career as a Michigan Wolverine.

On national television, then U-M head coach Brady Hoke watched Morris stumble while walking back to the huddle after suffering a staggering hit while throwing in a game against Minnesota in 2014.

Many U-M fans and officials in the stadium suspected that Morris suffered a concussion. He had to be held up by one of the offensive lineman. After regaining his balance, Morris waved off Hoke — Morris thought he was good enough to continue.

He was not.

One play later, Morris nearly threw an interception. He was visibly distressed and taken out of the game. Then, Hoke reinserted Morris after three plays.

In the days following, Hoke's player management was heavily scrutinized. Two days later, U-M's athletic director apologized for the handling of Morris. The U-M quarterback did have a concussion.

Hoke was fired, and replaced by Jim Harbaugh. Morris' playing career in Ann Arbor was over.

CMU offered Morris an opportunity to advance his career in a football sense — academics were secondary.

The Chippewas were stacked with upperclassmen on offense and defense, but there was a huge question mark surrounding quarterback. Who was going to replace Cooper Rush? The 6-foot-3, 230 pound Rush, a standout from Lansing Catholic, had just graduated as the all-time greatest quarterback in CMU history. Rush threw for almost 13,000 yards and recorded 95 touchdowns as play caller. He left no immediate successor.

CMU and Morris began discussing the Chippewas' quarterback problem. By Jan. 21, all were convinced that Morris was the answer. A flashy announcement from Morris' Twitter account heralded "a new beginning" for him at CMU.

A four-star recruit from De La Salle Collegiate, he was the third-ranked player in Michigan in the Class of 2013. After graduating from U-M in 2016 with a bachelor's degree in sports management, Morris, at 6-foot-3, 210 pounds, could provide what Bonamego and his staff were looking for – a strong-armed QB who could make every throw in CMU's new spread offense. He slipped right into what he called the “perfect fit" for offensive coordinator Chris Ostrowsky’s explosive offense, and the wide-receiving corps were poised for a highly productive season.

“For whatever reason, things just never clicked (for Morris) at Michigan,” Bonamego said. “He could have taken his degree and gone to work, but he wanted to give it one last shot.”

The underlying story, however, is something that most football fans are rarely told.

To lure Morris to play in Mount Pleasant, he was offered a scholarship to begin a master's program at CMU that he had no immediate intention of finishing.

His only goal was to play in the NFL.

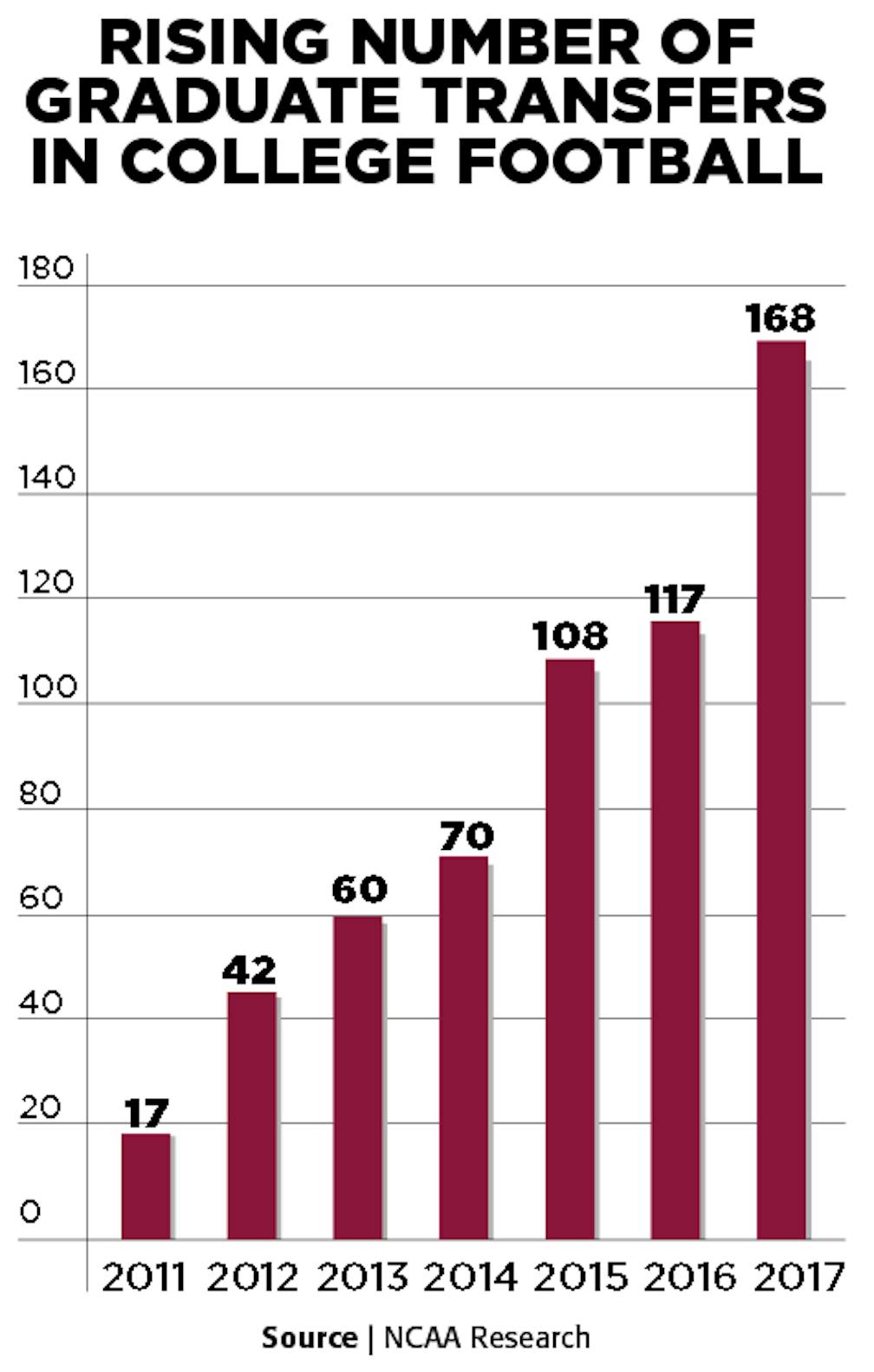

In 2017, Morris became one of 168 players who received similar scholarships to transfer to smaller universities, enroll in nine credits worth of classes and help energize otherwise struggling programs. He was one of the 72 percent of graduate transfer football players who enrolled in programs they abandoned after two years, according to an October 2015 NCAA Research study.

In the Mid-American Conference, most graduate transfers have failed to perform at a Power Five school. They decide to accelerate their degree progress to transfer to less high-profile teams in college football. Just this season, the MAC picked up former Michigan wide receiver Drake Harris, former Michigan quarterback Alex Malzone and former Iowa quarterback Tyler Wiegers – all examples of hyped recruits who didn’t live up to their potential.

Coaches in Mount Pleasant knew that Morris wasn’t going to stick around past football season, but the athletics department eagerly paid for his semester of study.

Morris made his debut as starting quarterback on Aug. 31, 2017 in a triple-overtime 30-27 win over Rhode Island in Mount Pleasant. After being responsible for six of eight turnovers in the 37-14 loss to Wyoming at the Famous Idaho Potato Bowl on Dec. 22, 2017, Morris left CMU for Miami to begin training for the NFL Draft.

Morris was not drafted.

Ruling background

Morris was just one of many graduate transfers around the country who accept scholarships as a last-ditch effort to make the pros, despite having no immediate intention of earning a graduate degree.

It's a trend that many coaches at smaller universities are taking advantage of to help bolster struggling programs, but not all NCAA administrators approve of the tactic.

“It is clear that students are transferring solely for athletic reasons,” Mid-American Conference Commissioner Jon Steinbrecher said. “The whole idea behind this graduate transfer exception was to transfer for a specific academic reason.”

In April 2006, the NCAA ruled that college athletes who have already graduated, but did not use all four years of eligibility, could transfer to another university and play without sitting out a game. Since the ruling, postgraduates looking for a chance to impress NFL or NBA scouts are choosing graduate school as an avenue to instead pursue a lifelong dream in professional sports.

Schools pay. Athletes play. Earning a graduate degree seems to be the least important part.

The average football recruit at CMU takes a redshirt in his first year. That means that they are on scholarship, but likely won't play in any games that season. A player practices and develops that season before starting their five-year eligibility clock.

Because of the timing, athletes who redshirt typically have their degrees completed within four years. Athletes also take summer classes. When they begin their senior season, if they have earned their undergraduate degree, they are eligible to transfer to another school and play one more season without sitting out.

The graduate transfer exception started in 2006 when the Division I Management Council and Division I Board of Directors approved new legislation allowing all student-athletes to transfer and play immediately after graduation. The student had to enroll in a graduate degree program.

In October 2007, another change was made to the rule from the Division I Management Council subcommittee. This standard said graduates could transfer and play immediately if their previous school didn’t object and they transferred into a specific graduate program that was not available at the previous school – an academic reason to transfer.

This rule, however, was manipulated by players and schools over time.

Graduate transfers began to claim slight differences in graduate programs to secure the opportunity to play football at another school.

“You saw kids starting to enroll in programs they really weren’t interested in,” Steinbrecher said. “The rule got changed so that it didn’t have to be for a program that wasn’t at your school. It just has evolved to where we are today.”

In April 2011, Division I adopted a proposal from the Mountain West Conference that allows graduate students in all sports to transfer and play immediately if it was their first transfer and their previous school did not renew their athletics scholarship.

After taking a recruit in and developing them, CMU’s recruits stack up against anyone in the country, Bonamego said. He used to be against recruiting graduate transfers because he felt it sent the wrong message to younger players. Still, Bonamego could not deny that bringing players from Power Five programs to CMU could have an impact in the locker room and on the field.

“When I was watching this start to happen across the landscape of college football … I was more against it than I was for it,” Bonamego said. “When you see your competitors having success (with graduate transfers), you have to reconsider.”

Rising numbers

Before he became "The Train" while playing for the Seattle Seahawks, Thomas Rawls suited up for head coach Dan Enos during the 2014 CMU season. The Flint graduate transfer's time at CMU might be best remembered for pleading guilty to attempted larceny in a building at Soaring Eagle Casino. The opportunity to add the former U-M power back Rawls to a middling offense was too good to pass up.

“(Coaches) can pick somebody who has a proven record, who (they) don’t have to develop and who can step in to a particular slot that they have missing,” said Jeri Beggs, faculty athletics representative and professor of marketing at Illinois State, who served on the NCAA Committee on Academics.

Rawls delivered on the field, but not in the classroom.

He played nine games and totaled 1,103 rushing yards and 10 rushing touchdowns for the Chippewas. But Rawls could not participate in the Bahamas Bowl game that season because of an “academic issue,” as CMU athletics described it. The Chippewas lost to Western Kentucky 49-48 on Christmas Eve on national television.

Acquiring transfer student-athletes has now become a standard operating procedure at Central Michigan and other universities around the country. From 2011-2016, the number of graduate transfers increased by 588 percent.

The 2017 CMU football team had two graduate transfers – Morris and defensive back Darwyn Kelly. This season, the Chippewas have four on the roster — Sean Adesanya, Marcus Griffin, Xavier Crawford and Ryan Tice, who arrived at CMU two days before the first game of the season.

Eligibility loopholes

Despite being called graduate transfers, the students do not transfer any credits. They have earned undergraduate degrees and are enrolling in graduate school.

For the average undergraduate athlete in NCAA Division I, to be eligible to play during the fall semester a student must earn their eligibility in the most recent semester that they have taken classes. For example, if an athlete wanted to be eligible to play football, they would have to meet the NCAA requirements in the summer semester from the same university that they would be playing for.

Graduate transfers do not take summer classes. They enroll for the fall semester. Since they did not previously attend their new university, fall eligibility comes from earning an undergraduate degree at a different university.

In theory, graduate transfers can play every regular season game of the fall semester without even attending classes. Most schools employ weekly and monthly academic performance evaluations, but according to the NCAA, the player is eligible to compete for entire fall season. Without individual punishment from the head coach or university itself, a graduate transfer football player could suit up for every game without attending a class. They only have to be enrolled in nine credits.

If attracting NFL attention is a player's reason for transferring, what would keep them from skipping class altogether?

“My sense would be that our schools would address that if it was an issue,” Steinbrecher said.

Postseason play is where it gets tricky. To be eligible for postseason play, the graduate transfer must have complied with NCAA standards during the fall semester. Final grades can come in before the football team’s last game of the season, so the athletics department has to make sure that everyone passed enough classes in the fall semester to be eligible.

As CMU football fans remember, Rawls never had a problem suiting up during the regular season, except for the one-game suspension he served related to his criminal case. During postseason play, his “academic issue” was discovered. Rawls was enrolled in nine credits, but one of his classes was a pass/fail class, so it did not count towards his required credit hours.

“It gives the appearance of kids being in school and not really being students at the same time they are athletes, and that becomes an issue,” Steinbrecher said.

Academic issues – not attending classes and failing classes – could be the reason that many graduate transfers around the country disappear during postseason play. Most of the time you don’t see a graduate transfer in a bowl game, the absence is credited to not wanting to get hurt before the NFL Draft.

“If a student is on one of our team rosters, they need to be a student,” Steinbrecher said. “They need to be attending classes.”

NCAA Research

In 2007, only 384 of 19,586 Division I football players were postgraduate students. Since then, the number has more than doubled. In 2014, there were 803 postgraduates.

The NCAA’s intention was that a graduate transfer would be an academic decision, however, most football players transfer to compete, not to earn a graduate degree.

“Clearly, the rule is being used in a way that wasn’t envisioned,” Steinbrecher said. “This wasn’t the intent when that rule was put in.”

Morris never anticipated a stop at CMU on his journey to the NFL. When his dream to become an NFL quarterback seemed within reach, he left Mount Pleasant to pursue it. After training in Miami for the 2018 NFL Draft, Morris was not selected and did not receive any long-term opportunities in professional football.

Morris, however, wasn’t interested in staying in the graduate program either. Since he already had an undergraduate degree from U-M, he didn’t want to take on student loan debt to finish his graduate program at CMU.

“If you have got a guy who has the opportunity to play in the NFL, he’s going to take that opportunity," Morris said. "A lot of the guys that are doing this just graduated from college debt-free. … They have their degree — they are good. If they want to finish their master’s program they have to pay these master’s program fees, which are insane."

Graduate students aren’t guaranteed academic aid in the second year of graduate school, following their last year of eligibility. Universities seem to be interested in paying for the athletes' classes only while they are competing.

“My master’s program was 36 credits. I’m not finishing 36 credits in a year. So, if they want to crack down on (graduation rates), pay for the whole master’s program," Morris said.

The NCAA found that postgraduates who are offered athletic aid after their eligibility is up are more likely to complete their degree program than those who do not receive post-eligibility aid.

Rachel Blunt, CMU associate athletic director who oversees student-athlete services and compliance, was asked whether specific students would receive any academic aid from the athletics department if their eligibility was expired but they wanted to continue their education. She said she had never dealt with a situation like this – every graduate transfer athlete who has come to CMU did not want to continue their education.

When these graduate transfer students leave after football season, the money from their scholarship is used as a "midyear replacement." Using this replacement exception, the graduate transfer’s scholarship is awarded to a walk-on or athlete who enrolled in the spring semester, without going over the 85 total counting scholarships in college football.

The NCAA reported that 51 percent of graduate transfer student-athletes receive degrees within two years. For football, that number is smaller. Only 28 percent of graduate transfers receive a graduate degree within two years. Those students were, on average, enrolled in 9.6 credits each semester and only earned 7.1 of those credits.

Those student athletes are, Steinbrecher said, taking advantage of the NCAA legislation. He acknowledges the graduate transfer exception is being misused. He should know —Steinbrecher served on the NCAA’s Transfer Working Group, a committee which focused on creating the latest, proposed transfer legislation.

Made public by the NCAA on Oct. 5, the Division 1 Council is introducing new transfer legislation that will have a massive effect on graduate transfers in football and basketball. The new legislation proposes that now, if a university takes on a graduate transfer, that athlete will count as one of the 85 scholarships for the first season and the following season, no matter if the student only has one year of eligibility remaining.

Fans will no longer see three or four graduate transfers on the same team, because that would mean in the next season, the program has three or four less scholarships to offer new students. The proposed legislation will enter the Division I legislative cycle for voting in 2019. According to the NCAA press release, most new rules are adopted in April.

If the Council approves this legislation in 2019, head football coaches around the country will now have to consider if a graduate transfer prospect is worth two years of scholarship money for one year of eligibility.

“I think it will slow it down,” Beggs said, who also served on the Transfer Working Group. “I do not think it will stifle it completely.

"Would a coach be willing to lose the (scholarship) count for two years? I think for the right player they are still going to do that.”