Various Central Michigan University institutions discuss name change policy

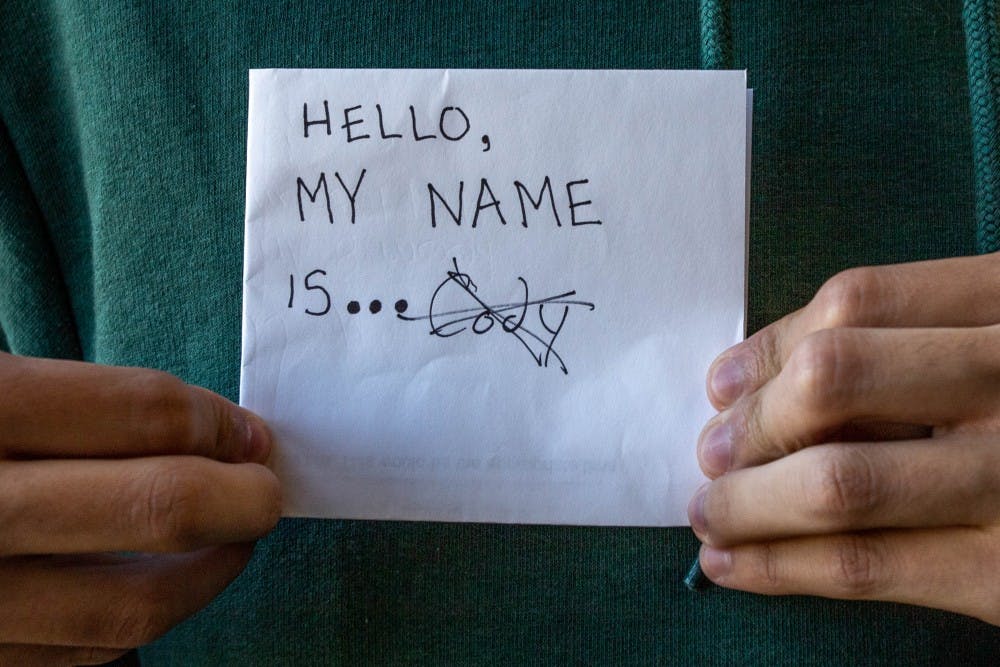

Within a few weeks of Emily Price’s room placement with male roommates at Central Michigan University, someone vandalized a sign she’d created for her door.

On her sign, someone had scrawled hate speech: the f-slur.

A year later, the North Carolina sophomore filed a petition for a legal name change. She was required by law to put her birth name, new name and address in a local newspaper announcement of her hearing.

The decision instilled fear into Price; she didn’t want people to know where they could find her if they were intent on harming or intimidating transgender people.

People looking for a legal name change can request its hearing be kept confidential, but a judge can decide to deny the request if they don't believe the notice would put the petitioner at risk.

Without documentation of a legal name change, CMU students cannot change how their names appear on their student emails, Central Cards or class rosters — but changes to this policy might happen soon.

The Registrar’s Office recently formed a committee to explore a change to the university's name policy.

Chief Diversity Officer A.T. Miller said the proposed changes would allow students and staff to choose a preferred name on everything except for cases where a legal name would be needed, such as federal student aid forms.

The board’s proposed changes are being investigated by the Office of Information Technology to determine costs and logistics that would be associated with the change.

Shannon Jolliff-Dettore, director of the Office of LGBTQ Services and member of the committee, said the proposed change would provide support for students.

“The name change policy serves as a piece of validation and recognition for our trans students as well as all those that will benefit,” Jolliff-Dettore said. “Change is coming.”

Students have also been fighting for the policy change. Registered Student Organization Transcend and the Student Government Association have spearheaded this action.

SGA Diversity Chair Gabrielle Mason is heading a project to propose legislation supporting the change in policy. Mason is in the exploratory phase, gathering information on how other similar universities have enacted similar changes.

Isabella County Prosecutor Stuart Black, who is running for probate judge, said in a Monday meeting with SGA's Diversity Committee that the current legal process is too difficult for this change to be implemented.

Mason will be consulting with Black for guidance due to the influence of state law on students.

While the policy can affect cisgender students as well, transgender students are more likely to be affected by a restrictive name policy and can encounter unique safety concerns.

The Williams Institute at UCLA estimates 0.6 percent of US adults are transgender.

This estimate of 0.6 percent would put CMU’s on-campus transgender population at 109 people — but the actual number may be higher since younger generations are more likely than the general population to identify as LGBT, according to research conducted by Gallup, GLAAD and others.

These students can find themselves in a conundrum: they can either put themselves at risk of having others find out they’re transgender when they use their student ID or they can pursue a legal name change that could potentially announce to strangers both their address and transgender identity.

It’s a risky choice for members of a community that is susceptible to hate crimes and experiences a 47 percent lifetime sexual assault rate, according to the National Transgender Equality Center's "2015 U.S. Transgender Survey."

Along with these concerns, the costs and legal process associated with name changes can be difficult for college students. The petition filing fee at the Isabella County Probate Division is $185. A newspaper announcement is an added $63.50. Changing other legal identification documents can also carry a cost, like the $50 application fee for birth certificate changes.

For those who can afford the costs, the name change can improve a student's quality of life.

Massachusetts sophomore Jace Parker once had a student employee see his ID and ask him, “What’s in your pants?” Another time, a worker asked him why he would choose to be transgender and told him how sad it was he was “mutilating” his body.

Most of the time, Parker felt he was being seen as fundamentally different when he used his student ID.

Eventually, he grew so frustrated with his experiences he used a permanent marker to black out his birth name and ID photo that had been taken before he started testosterone.

After Parker wasn’t able to swipe in for a meal due to his blacked out ID, he got a new one. With a picture that looks more like him now, Parker doesn’t experience as many difficulties as he had before — but the name on the ID is still the same.

Parker, a residential assistant at Robinson Hall, never emails his residents because he doesn’t want them to know his birth name. He emails every professor before classes start to let them know what name he goes by — but he still feels anxious on the first day of class. Every experience with a new professor comes with the fear he will be called by his birth name and be seen as different by other students.

Price has lived this fear: one professor called her by her birth name for weeks after she had told him what name she used.

Aside from concerns of staying physically safe or avoiding awkward situations, a more broad topic is at hand: identity.

“Your name is your identity,” Mason said. “If you’re not called by your specific identity or what you’re looking to be identified as, I would not classify that as being safe (at CMU).”

Miller echoed these sentiments, saying matching personal identity to what others see is imperative.

“People’s names are fundamental to identity so it’s an important aspect of inclusion,” he said.