'You are not alone': A guide to the resources, support systems and processes available to students impacted by sexual assault

What to do when the worst happens

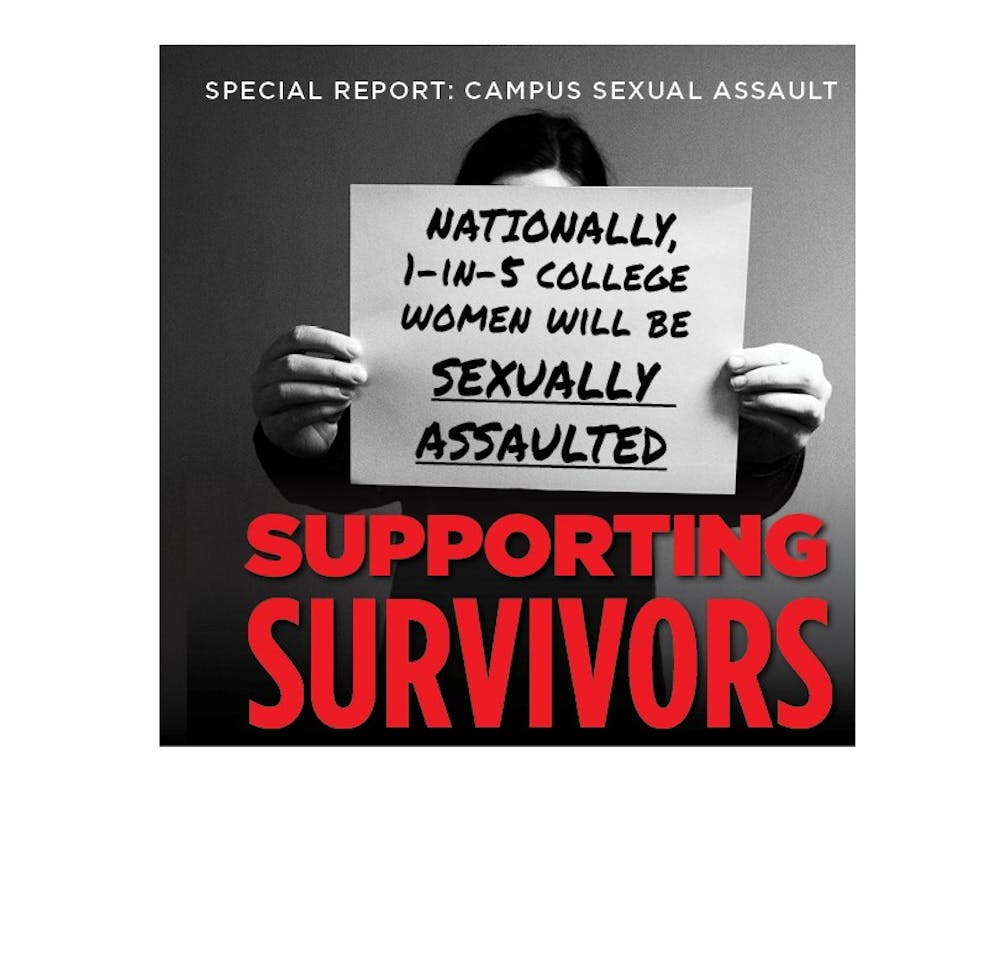

One-in-five women and one-in-16 men are sexually assaulted while in college, according to the National Sexual Assault hotline.

There were 16 cases of rape and 13 cases of fondling reported to the Central Michigan University Police Department in 2018, according to the Annual Security and Fire Safety report published on Sept. 30.

That is not the whole story. A 2014 report by the U.S. Department of Justice showed that only about 20 percent of college-aged women reported their sexual assaults to law enforcement.

More than 50 percent of sexual assaults at universities occur in August, September, October or November, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network. Statistically, students face a higher risk of being sexually assaulted during that period of time that is sometimes referred to as the “Red Zone.”

It can happen anytime

Nationally, the Red Zone is a time that law enforcement has identified to increase awareness about the threat of sexual assault.

At Central Michigan University, administrators have taken a different stance.They want students to be informed about sexual assault prevention and resources available to survivors all year long.

Brooke Oliver-Hempenstall, director of Sexual Aggression Peer Advocates (SAPA), Mary Martinez, Title IX Coordinator and interim OCRIE Director and Larry Klaus, chief of CMUPD, fight to help sexual assault victims every day.

They want to remind students that sexual assault prevention and how to support survivors are issues they should be aware and cautious of at all times—not just during the Fall semester.

“This time of year may be a time when students may be a little more vulnerable, but we’re looking at the whole calendar year, and hope that we can take the necessary precautions,” Klaus said.

Klaus said it’s important for students to trust their instincts and to be aware not just of themselves, but of their friends too.

“Look out for each other,” Klaus said. “If you see something out of the ordinary, or you see one of your friends getting into a situation that you know otherwise they probably wouldn’t want to be in—well that’s your time to step up, and intervene and maybe extract them from that situation.”

Unfortunately, no matter how careful someone is, the worst could still happen to them. Even if they trust their instincts, are consciously aware of their environment and surround themselves with people they trust—even if they do everything “right”— they can be sexually assaulted.

If that does happen, the most important things for that student to understand are: CMU has resources to support you and to know that you are not alone.

“I want people to be conscious of the fact that there are so many resources and supports on campus—if something does happen that they don’t have to go through it alone,” Martinez said. “There’s SAPA, counseling Center, CMUPD, my office OCRIE—there are resources available so that if someone did experience something or knows someone who experienced something during the “red zone” or prior to CMU, or after the red zone, that all those resources are there all the time.”

What can I do if I’ve been sexually assaulted?

If a person has been sexually assaulted, there are many different resources available to them and processes they can use if they choose to.

There is no single cookie-cutter process for dealing with the aftermath of a sexual assault— survivors can choose to do whatever feels right for them.

While there are many resources for sexual assault survivors at CMU, the three biggest departments at a survivor's disposal are CMU Police, OCRIE and SAPA. All three offices can help students with the aftermath of an assault, and each office has a different process and policy for addressing assault.

Central Michigan University Police Department

If a student chooses to contact the CMU Police Department to report an assault, Klaus said one of the first things they’ll be told is that what happened was not their fault.

“For us, CMU Police, we go on the premise of, ‘It’s not your fault, and we believe you,’ and that’s the premise of how we’re going to conduct our investigations if you engage the CMU Police Department,” Klaus said. “We want to look at an offender-based type circumstance versus focusing on the reporter.”

Speaking from the perspective of law enforcement, the first thing Klaus recommends a student should do after they’ve been assaulted is get a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner, or SANE exam done if it’s in the period of time evidence can be collected, which is 120 hours or five days. The evidence collected in the exam can help officers put a criminal case together to present to the county prosecutor.

SANE Exams are free through the state of Michigan, and it is a head-to-toe exam that typically takes as long as three to five hours to complete. Sometimes it could last longer or shorter than that depending on the nature of the assault.

Oliver-Hempenstall said that it’s important for people considering a SANE exam to keep in mind that while the recommended time frame is 120 hours, sometimes the examiner still may be able to collect enough evidence even past that time frame, depending on the nature of the exam, so it’s still worth getting one. Likewise, while it’s recommended that survivors should not shower or change their clothes after being assaulted until after the SANE exam, it’s important to know that viable evidence can still be collected even after a shower.

During the exam, the survivor can opt-out of any part that they are not comfortable with, as it’s extremely extensive and intrusive. Swabs, pictures, notes, genital exams. A survivor has the right to have a support person in the room with them, whether that be a friend, family member or a SAPA, to be there with them in case they want to take a break or decide not to continue.

As part of the exam, the survivor will be tested for any sexually transmitted infections or pregnancy and will receive medications for STIs.

If the survivor suspects they may have been drugged before the assault, Oliver-Hempenstall said they should mention that to the examiner, even though most date-rape drugs tend to leave the body’s system quickly. The examiner should then take blood and urine samples, which could be helpful if the survivor decides to engage law enforcement.

After the SANE exam, a survivor can choose to have it turned over to law enforcement if they wish to proceed with a criminal investigation. The hospital will hold the results from a SANE exam for up to a year. At the end of the year, if they still have the exam, the survivor will be asked if they want it to be turned over to law enforcement before it is disposed of.

After law enforcement receives the SANE kit, it is sent to the state police lab for analysis, Klaus said. They’d examine any DNA, which would be put into the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, where they’d look for a “hit” on any comparable DNA in the system.

Having the evidence collected in a SANE exam is often beneficial to officers while investigating an assault. However, Klaus doesn’t want to discourage anyone from reporting a sexual assault if they did not get an exam done within the first 120 hours after the assault.

“We can still put together a viable case to present to the prosecutor in the event that they want to pursue a criminal investigation,” Klaus said.

Police officers often have a brief interview with someone at the hospital during their SANE exam, especially if the assault happened very recently, to help process their trauma, Klaus said. The officer would then schedule a more in-depth interview for a few days later after they’ve had a couple “sleep cycles” and are more cognitively aware of the situation. This way, Klaus said, victims aren’t providing statements while in trauma.

After the victim gives their statement, the police proceed with an investigation. The exact steps taken in an investigation vary greatly in every case, but often the police will interview any possible witnesses, collect evidence from the scene of the assault and collect evidence from the victim such as clothing.

In addition to putting together a case, Klaus said the officers connect survivors with supportive resources like SAPA and OCRIE who can help them emotionally.

“There may be some bleed over into their academics. You know it’s a traumatic event, you got enough going on, with going to school, trying to work, and then you have this significant event take place in your life—we understand. There are things that we can do to help our students be successful so that they can continue their education here at the university,” Klaus said.

If a survivor is worried about their safety, the officers will help them set up a ‘safety plan,’ Klaus said. That usually includes making sure their social media pages are private, the offender is blocked, issuing a trespass notice for the offender if they aren’t from CMU so they won’t be able to come on campus, changing living or class assignments if needed, issue a Personal Protection Order or whatever else they may need to do to help the student feel safer.

While survivors do have the option to involve law enforcement after an assault, Klaus noted that they don’t have to. Survivors have the right to choose what they want to do each step of the way— they do not have to speak to law enforcement, even if they want to have a SANE exam completed.

Office of Civil Rights and Institutional Equity (OCRIE) and Title IX

All U.S. schools that receive federal funding are required to follow Title IX, a civil rights law that ensures equal educational access for all students and prohibits gender discrimination. The Office of Civil Rights and Institutional Equity at CMU, which includes the Title IX office, is where a student would need to go in order to file a sexual assault report with the university and receive advice regarding the policies and procedures the university can take. The office is located in the Bovee University Center, room 306.

Martinez, as the Title IX coordinator and interim director of OCRIE, receives reports of sexual misconduct and is a resource to CMU students.

“The university’s definition of sexual assault might be different than the criminal statute or what rises to a criminal level. So understanding that, if a survivor does not want to proceed criminally or if the case isn’t moved up to be prosecuted criminally, there’s still the university’s sexual misconduct policy, which defines sexual assault. It’s something that the university could look at and address, and often does,” Martinez said.

If a student wishes to speak with someone in the Title IX office, they can call, email or utilize CMU’s online reporting tool.

A survivor can choose to proceed with an OCRIE investigation in addition to a criminal investigation, or just the OCRIE process if they want to. Martinez noted students should know that though something might not be sexual assault under the criminal statue, it might still fall under the sexual misconduct policy.

“It’s really up to the survivor on what they want to see and how they what to proceed and what’s best for them,” Martinez said. “From the university’s process, whenever OCRIE is informed of any type of sexual misconduct that occurs involving our students or faculty or staff, our first response is to provide resources and outreach to the survivor so that way they have information so that they can make an informed decision about what is going to be best for them. Ultimately one of OCRIE’s goals is to help that survivor be as successful as they can be.”

OCRIE typically first reaches out to a survivor through an email, Martinez said, or a “resource letter.” It describes what OCRIE is and provides contact information for resources like SAPA, the police and the counseling center.

After the resource letter is sent, Martinez said they follow up with the survivor, again through email, to give them the opportunity to meet Martinez as the Title IX coordinator or one of the staff members for a “resource meeting.” During that meeting, the survivor is informed of all the resources available to them, as well as any interim measures the university can take to help them. For example, Martinez said if the survivors live in the same residential hall as the person who assaulted or harassed them, they can be moved to a different hall. Academic accommodations can also be made if they’re in the same classes.

“That’s what’s discussed in that resource meeting: What does the survivor need, and how can the university help that survivor get what they need to be successful?”

Martinez said OCRIE’s process is explained in that meeting, and the options survivors can choose to partake in that process, whether that be to proceed with the OCRIE investigation, a police investigation, or nothing. Survivors are encouraged to think about all options, talk to their support system, and choose what’s best for them, Martinez said.

“One thing I don’t ask at that meeting is what happened. If someone wants to share information, we’re always listening, but I’m not going to have a survivor tell their story if they’re not ready to, if they’re not sure if they want to move forward with an investigation,” Martinez said. “We really strive to only have someone only tell their story one time, if possible, to anyone at the university.”

If a student does choose to proceed with an OCRIE investigation, they would start by giving an official statement to Martinez or another staff member. While each OCRIE and Title IX investigation is different, the investigators typically question everyone involved including any witnesses and evaluate any evidence available before eventually coming to a conclusion. At the end of an investigation, Martinez lets the victim and possibly the assailant know what the conclusion was. If needed, Martinez can inform the Office of Student Misconduct of the findings and can recommend what actions she believes should be taken, such as dismissing the assailant from the university.

Martinez said it’s important for students to remember that under Title IX, there is no time frame limiting when a survivor can make a report.

“So if you want to report something that happened your first semester on campus and now it’s your last semester, you can still come forward and report, and we can still fully investigate if that’s what the person wants to do,” Martinez said.

Sexual Aggression Peer Advocates (SAPA)

SAPA is a 24/7 survivor-centered, paraprofessional student organization at CMU that offers services including a confidential support line, online chats and direct in-person assistance throughout the fall and spring semester. The program was created at CMU 22 years ago, and it was the first of its kind to exist on a college campus.

SAPA members can provide survivors with a step-by-step explanation of all the options available to them, from counseling referrals to medical and law enforcement assistance.

“We’re meeting people where they’re at— so it might be they’ve reported and they need support going to police, they need an advocate to go with them, or maybe to the hospital – that’s where SAPA can help,” Oliver-Hempenstall said.

Oliver-Hempenstall stressed that while SAPA is a valuable resource, they do not provide advice or tell somebody what they should do. They meet somebody where they are at and try to assist them where they can, which is also her role.

“Sometimes they just need to talk because it’s 3 a.m. and they don’t know what is going to happen," Oliver-Hempenstall said. "So (SAPA) is providing support at whatever process they’re in, at whatever stage they’re in, and whatever choice they’re making.”

You are not alone

While the offices Klaus, Oliver-Hempenstall and Martinez work for all have different processes when it comes to addressing sexual assault, they all agreed there is a single important takeaway they want survivors to understand – they are not alone.

There is an abundance of confidential, and non-confidential, resources and people at CMU and in Mount Pleasant who are there to help survivors. There is support for survivors – people who will be there for them – while they figure out what they want to do.

“There’s no ‘right way’ to handle and deal with and cope with trauma," Oliver-Hempenstall said. "So often times it is quite frankly normalizing this experience and understanding that unfortunately so many folks have experienced assault, and finding the right ways for folks that best help them cope and manage with their life, with the stress, with the process of what they’re going through, and it’s going to be different for everybody."

For survivors struggling to cope with their trauma, the counseling center is a resource that not only provides counseling appointments but a sexual assault and domestic violence support group that meets every Monday afternoon.

There are many resources and options at CMU available to survivors after an assault, no matter how they choose to proceed.

“We’re here for you, quite literally, at 3 a.m. or 3 p.m. or whenever you need us," Oliver-Hempenstall said. "We are here for you."

Confidential resources

· CMU Counseling Center, Foust Hall 102 (989)-774-3381

· CMU Sexual Aggression Peer Advocates (SAPA) AVAILABLE 24/7 (989)-774-2255

· CMU Student Health Services, Foust Hall 200 (989)774-6599

· Listening Ear (989)-772-2918

· McLaren Central Michigan – McLaren Health Care (989)-775-1600

· Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE) (989)-772-6700

· Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe Nami Migizi Nangwiihgan Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking/Harassment Services (989)-775-4400

· RISE Advocacy, Inc. (844) 349-6177

Non-confidential resources

· Office of Civil Right and Institutional Equity, Bovee University Center 306 (989)-774-3253

· CMU Police Department, 1720 E Campus Dr. (989)-774-3081

· Isabella County Sheriff’s Department, 207 N Court St. (989)-772-5911

· Mount Pleasant Police Department, 804 E Hight St. (989)-779-5100

· Saginaw Chippewa Tribal Police Department, 6954 E Broadway St. (989)-775-4700