Bono-fide Chippewa: Bonamego wouldn't change walk-on career if he had the chance

During his college football career, John Bonamego didn’t score touchdowns on Saturdays or have a scholarship paying his tuition. When you ask him about his collegiate football days, he said he wouldn’t change it if he had the chance.

After walking onto Central Michigan University’s football team and graduating from CMU in 1987, Bonamego began a coaching career that took him to the sport’s highest level and ultimately brought him back to his alma mater — three collegiate and five NFL assistant coaching jobs later.

“I’ve wanted this job for a very long time. I plan to start and end my head coaching career here,” Bonamego said when he was introduced as CMU’s 28th head football coach on Feb. 9, 2015.

Back on the sidelines of Kelly/Shorts Stadium in the familiar softness of mid-Michigan’s autumn sun, CMU’s second-year head coach is in the thick of living his dream. Whistles blowing and shoulder pads clashing together, Bonamego is in his element. Arms crossed and glasses on, he stalks around his team’s practice, less than a week removed from a 49-10 loss to rival Western Michigan, with a coolness that makes you feel he knows something you do not. He stands back in observation, allowing the coaching staff he assembled to do its job, preparing the Chippewas for a Homecoming matchup against Ball State.

A 5-foot-8, 160-pound quarterback from Paw Paw High School in 1983, Bonamego, like many young football players, wanted to make it to the NFL. He was not heavily recruited by colleges in high school.

His coach at Paw Paw, Don Moorhead, who played quarterback for Bo Shembechler at the University of Michigan, did not tell Bonamego “a whole lot back in those days” about how to get recruited.

Hope College, Grand Valley Sate and Ferris State all offered Bonamego scholarships. He even had an offer from U-M assistant coach Gary Moeller to walk on at Michigan. He didn’t take the offers.

Bonamego watched his first game in Kelly/Shorts Stadium the summer before his senior year of high school on Sept. 4, 1982 — a 35-10 CMU win against Indiana State. For him, it was “love at first sight.”

“Everybody wants to play someplace where football is important — where they have tradition,” he said. “My first time visiting Kelly/Shorts Stadium, it was the entire fan base (that impressed me). The student section was outstanding. (CMU) had a winning tradition and an iconic head coach, (Herb) Deromedi.”

Competing with Division I athletes for the first time, Bonamego said the start of his college career was a shock, but he never felt incapable of competing.

“It definitely can be intimidating being at a (Division 1) practice for the first time — especially as a walk on,” he said. “Back then, everything we did was in full pads. It was physical, but you were always treated with respect.”

When practice began, he was given black cleats by long-time CMU equipment manager Dan Bookie. The rest of the team was wearing white cleats, Bonamego said. It was the way he carried himself with confidence that allowed him to keep up with the scholarship players.

“Image is how you see yourself. Identity is how you’re perceived by others. I never saw myself as not belonging,” Bonamego said. “I prepared that way and competed that way, so that became my identity.”

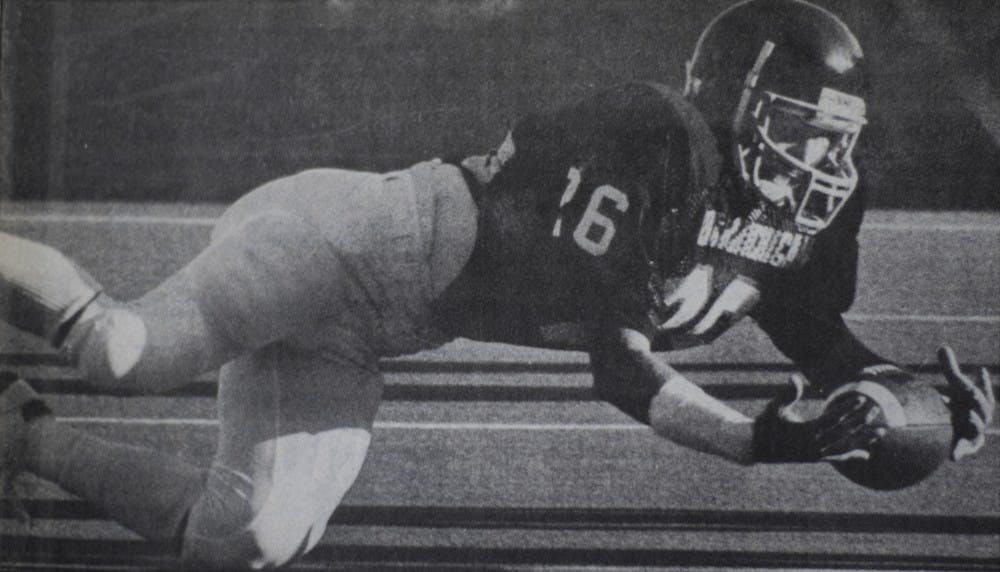

As a Chippewa, Bonamego saw time at about every skill position on the field, playing quarterback, wide receiver, defensive back, slot back and running back in practice. Opportunities to play in games came sparingly.

“My goal was to be a starter here up until the very last practice that I walked off the field,” Bonamego said. “That’s what I was always working toward. I never gave up on that.”

Neither a scholarship nor playing time were in store for Bonamego. A block on a strong safety he made that sprung a CMU running back for a touchdown in the fourth quarter of a blowout game during his senior season is one of Bonamego’s fondest memories of game action — fitting his team-first mentality.

He won the Iron Man Award, an award given to the team’s best practice player, twice and was named the lone captain for his senior Homecoming game.

Size was Bonamego’s biggest issue. He said it affected his on-field ability “in every way.”

Being the smartest player on the field, Bonamego said, was how he made up for his size disadvantage.

“I always knew what I was supposed to do,” he said. “It was never going to be a matter of me not knowing what to do or how to do it or giving the right effort.”

Worried about her son playing football because he was smaller than other children, Bonamego’s mother, Rita Bonamego, said she couldn’t be prouder of her son.

The former Red Cross nurse teared up when she saw her son on the field at Kelly/Shorts. With a thick accent that shows the family’s northern-Italian roots, Rita Bonamego said her son dreamed about coaching CMU since he was in college.

“We have been proud of him because he did reach his goal and he did what he dreamed of doing, which not many people are able to fulfill in their lives,” she said.

Off the field, football rarely left Bonamego’s mind.

Former CMU student Buzz Famularo lived next door to Bonamego on the second floor of Thorpe Hall during the mid-80s. Famularo said Bonamego was frequently drawing plays and entertaining dormmates with passionate rants about his offensive playbook — earning him the nickname “Coach Bono.”

“He’d come in and sit down and inevitably, the conversation would go back to drawing up plays and talking about football,” Famularo said. “It was this tiny walk-on with all these big guys, drawing up plays from out of his head, saying ‘this is what we need to do.’”

Bonamego said he took his former head coach Herb Deromedi’s football-tech classes as a student. He always bothered the legendary CMU coach to look at Bonamego’s offense called “the pyramid.”

By his junior season, Bonamego realized he was not good enough to play in the NFL. He was interested in coaching. He shared his goal with Deromedi and looked to him as a mentor.

Bonamego said he “learned everything” from CMU’s all-time winningest head coach.

“(Deromedi) gave me a chance to be a part of a Division I football team,” he said. “He recognized me for my work. He allowed me to be dressed for games and play. I got the Iron Man Award twice. He gave me the honor of walking out as a sole captian at homecoming my senior year — that’s probably one of the top honors I’ve ever received.”

As a walk-on, Bonamego’s time with Deromedi was limited. Instead, he talked more regularly with his recruiting coach Denny McFlurr.

“Our relationship (Bonamego and Deromedi’s) definitely grew over the years,” Bonamego said. “He was always very honest with me. My focus was to make myself the very best I could be and (Deromedi) appreciated that and (was) always encouraging and communicating to me what I needed to improve.”

Now standing in Deromedi’s shoes, Bonamego said he “has empathy” for kids standing in the same shoes he stood in 33 years ago, but is also realistic.

“That’s the path I took, but we have to see enough in them to warrant the opportunity too,” he said. “This is a game where people get hurt and the last thing I want to do is put someone in a situation they aren’t physically able or gifted enough to protect themselves and their teammates.”

Walk-on long snapper Travis Malinowski said his head coach understands how hard walk-on players have to work.

“He understands the effort and determination required to play college football as a walk-on and how special it is to be a part of the CMU family,” Malinowski said. “As part of the team, we have the same goals and commitments as the scholarship players, and coach Bono treats us all the same. He always promotes a positive atmosphere for CMU football.”