Clarke Historical library speaker discusses children's book on Tulsa massacre

Carole Boston Weatherford stood at the podium in the Opperman Auditorium in front of a full house. The audience was captivated by her every word that defined spiritual hymns from the emancipation period. As Weatherford sang and it was the audiences' turn to respond, voices filled the silence in harmony.

Weatherford: "It's me, it's me, it's me oh Lord."

Audience: "Standing in the need of prayer."

"It's me, it's me, it's me oh Lord."

"Standing in the need of prayer."

"Not my father, not my mother, but it's me oh Lord."

"Standing in the need of prayer."

"Not my mother, not my father, but it's me oh Lord"

"Standing in the need of prayer."

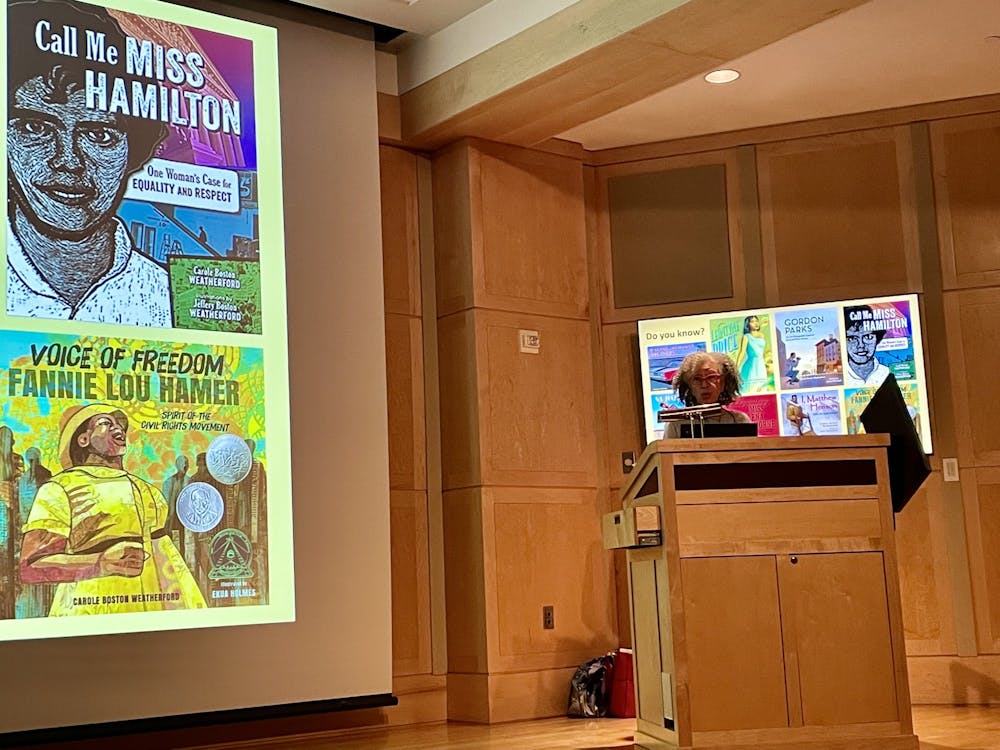

On behalf of the David and Eunice Sutherland Burgess Endowment, the Clarke Historical Library hosted its second speaker series event on Sept. 27 with Weatherford as guest speaker.

Weatherford is from Baltimore, Maryland, and currently works as a professor at Fayette State University in North Carolina. She is an author of over 60 books in poetry, nonfiction and historical fiction for people of all ages.

According to Weatherford, she utilizes her writing as a way to amplify marginalized voices. She said her mission as an author is to mine the past of family stories, fading traditions and forgotten struggles that center African American resistance, resilience, remarkability and remembrance.

"I choose subjects that are close to home ... or close to my heart. I write what I like to read and what I like to learn about," Weatherford said.

Most of her work revolves around children's books that include subjects such as slavery, segregation, civil rights or the Black Lives Matter movement. In her presentation, Weatherford mentioned that she frequently receives the same question: "Are children too tender for tough topics?"

"My response is always this: If children of color and LGBTQ+ youth can be victimized by haters, then other children can certainly learn about it and learn to empathize. Children deserve and will demand the truth, and the more they know, the more they want to know."

For her most recent children's book, "Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre," Weatherford was awarded the Coretta Scott King Award, which recognizes young adult and children's works written or illustrated by African Americans reflecting the Black experience.

Weatherford said she was inspired to write this book due to the history of the Tulsa Massacre being suppressed for over 75 years. In addition, the illustrator of the book, Floyd Cooper, has a grandfather who survived the massacre. However, Weatherford didn't know this until Cooper's passing in July 2021, shortly after the book release in Feb. 2021.

Weatherford was nominated for the Texas Bluebonnet award program, which encourages students in Texas to choose five books to read from a list provided by the Texas Bluebonnet Committee. Her work, "Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre," was nominated for this program. However, the Texas Bluebonnet Committee has banned the book -- not allowing students to read it.

Weatherford mentioned during her presentation that it is more common for books to be banned when the author or work involves people of color and LGBTQ+.

What was the Tulsa Massacre?

According to the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum website, Tulsa, Oklahoma was originally known as "Magic City" due to the abundance of oil farms. Greenwood District, a Black neighborhood in Tulsa, was especially successful in correlation to this.

On May 30, 1921, Dick Rowland, a young Black man, entered an elevator with an elevator tenant, Sarah Page, a white woman. Page accused Rowland of sexual harassment and Rowland was taken into custody the next day.

Once the local paper, the Tulsa Tribune, reported the story, two mobs formed. One mob was made of Black people trying to protect Rowland from being lynched and the other was made of white people trying to stop them. There was a confrontation between the two mobs near the courthouse, which the sheriff had barricaded. Eventually, the Black mob began to retreat to the Greenwood District because they were outnumbered.

On June 1, 1921, Greenwood was looted and burned by white rioters. Governor James Robertson declared martial law, and National Guard troops arrived in Tulsa to assist firemen in putting out fires and imprisoned Black Tulsans who were not already in custody. Over 6,000 people were held at the Convention Hall and the fairgrounds, some for as long as eight days.

Over 35 city blocks were charred ruins, more than 800 people were treated for injuries and reports of death began at 36. However, historians now believe as many as 300 people may have died.

Weatherford said in her presentation that after a recent investigation, 75 years later, it has been discovered that the worst racial attack in U.S. history was due to police and city officials plotting with the white mob to destroy the nation's wealthiest Black community.

Riot or Massacre?

According to the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, the Tulsa Massacre was originally referred to as the Tulsa Race Riot. However, it was only until recently that historians discussed what to call the event: riot or massacre?

In 1921, the massacre was referred to as a riot for insurance purposes. Calling something a riot prevents insurance companies from having to pay benefits. Therefore, those whose homes and businesses were destroyed in Greenwood had no way of receiving compensation, the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum said.

According to the museum, it was also common at the time for any huge clashes between different racial or ethnic groups to be categorized as race riots.

For any questions, email Weatherford at cbwpoet@gmail.com or visit her website.