CMU Health Clinic treatment fights infant mortality rate

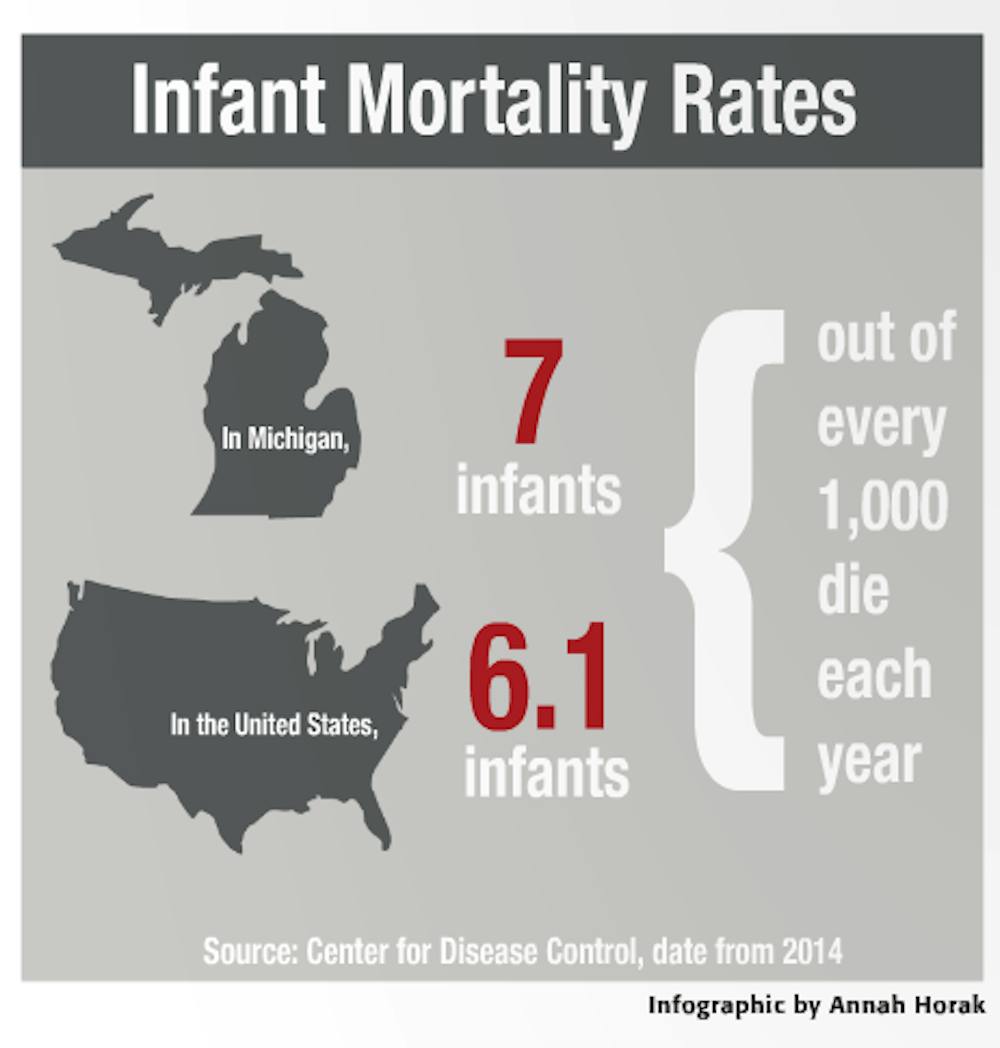

Almost seven out of every 1,000 infants born in Michigan die within a year — a figure that exceeds the national average of 6.1.

To combat that high infant mortality rate, physicians at Central Michigan Health are changing their approach to prenatal care. The facility, located in Saginaw, has partnered with the Centering Healthcare Institute and Michigan Health Improvement Alliance, Inc. to provide a group model of care for expecting mothers.

Dr. Erica Canales and Nurse Midwife Marilyn Filter, both in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, worked to bring the Centering Pregnancy program to Saginaw County — where 21 babies died within their first year in 2014.

“I’ve championed this for 10 years,” Filter said. “Part of the success is having the women encourage each other. Compliance with care increases because the women are empowering each other.”

Traditional prenatal care has physicians and expecting mothers have 10 short one-on-one appointments, Filter said. The Centering Pregnancy program also has a group of expecting mothers at similar stages of their pregnancy who meet together with physicians in 10 sessions for 90 minutes.

By meeting with physicians in a group, mothers receive roughly 20 hours of treatment compared to the traditional two. Twelve other hospitals in the state have already adopted the method.

“The driving force behind the questions and the discussion is not the provider telling mothers what to do — it’s the women themselves,” Canales said.

Groups comprise mothers with a variety of backgrounds such as patients who already have children, first-time mothers and young women.

“You get what they call the wisdom of the group, so between all of (the mothers),” Canales said. “Often times they are able to answer their own questions.”

The leading cause of infant death is pre-term birth. Hospitals that have adopted the Centering Pregnancy program have seen pre-term birthrates drop by 33 percent, Canales said.

“Our pre-term birthrate hasn’t dramatically changed in four decades despite many different medical interventions designed to reduce that risk,” Canales said. “With more time spent with providers and the support of the group, it has been indirectly shown, at least in some very large randomized trials, the pre-term birthrate is reduced.”

Taking care of a premature baby is not just an emotional burden for parents but a financial one, said Fields. The annual cost of treating pre-term birth is $26 billion, according to the U.S. Institute of Medicine.

“We want to save babies — that is the overall goal,” Filter said. “But in achieving that ultimate goal of saving life, we’re looking at significant cost savings to the community, insurance companies and families.”

The first group of patients is expected to meet in the middle of November. Canales hopes that students from the College of Medicine will be able to participate in the new method at some point in the future.

“We certainly hope as we collect data and observe the impact we’ll be able to get students involved,” she said.

Canales believes that Centering care provides a psychosomatic benefit to patient health, and could be responsible for the program’s improved results.

“We’ve known for a long time there’s a mind body connection. Pregnancy is not different from any other health condition in terms of our state of mind and its effect on our health,” she said. “There isn’t really any other explanation. We’re not giving medication differently. We’re just providing education, time and community.

“I think if you can give care in a way that gives you something to look forward to every week, even more than your usual clinic environment, that’s a real win.”