CMU assistant professor, students use mapping technology to recreate medieval city

(From left to right) Jake Hayward, John Frost and Scott de Brestian discuss the proper use of the RTK GPS/GIS unit, which is used to determine positions of archaeological features.

Central Michigan University assistant professor of art history Scott De Brestian and a team of archaeology students have started working on a 3D re-creation of the medieval city of Najera, Spain.

For the past four years, Brestian has spearheaded and co-directed the Najerilla Valley Research Project (NVRP) — an international multi-disciplinary project that looks at changes in human settlement in the province of La Rioja, Spain.

As archaeologists, they study human history through the excavation and analysis of artifacts and physical remains.

According to the NVRP webpage, the goal of the project is to investigate and understand the changes in settlement and material culture in the region between the late Iron Age and the 14th century.

"We want to discover how the presence of a royal court affects the development of a city," Brestian said.

The NVRP team’s experience and work can be followed through a series of blog post from 2015-2018.

You can learn more about the technology Brestian and his team used on the Spanish countryside, by listening to this Archaeotech Podcast.

According to the podcast's website, the team is "using some interesting tech to get them closer to a 3D model of the town they're investigating."

The city of Najera

In the middle ages, Najera was the capital and religious center of the kingdom Navarre. Today, the city is populated by about 6,000 people.

"I did my dissertation just north of (Najera and San Vicente del Valle)," Dr. Brestian said. "I became familiar with the area and some of the interesting elements of its history, so I decided it would be a good place for a project."

Brestian said the city had never been explored by archaeologists, making it a prime location for the project.

A picture of a 3D model constructed from the aerial drone photos, showing the topographical relief.

In 2013 and 2014, Brestian worked alongside Roanoke College's Victor Martinez and Spanish contract archaeologist Milagros Martinez in Spain to do research for the project. Three seasons of fieldwork followed.

The team aimed to study key structures and features of the medieval city, like the Jewish Quarter, a castle and caves in the cliffs.

"We started off thinking 'there are a lot of interesting things here, but we could do it fairly quickly,'" Brestian said. "The more we looked, the more we would find."

Brestian said the Jewish Quarter was a prime location for finding things like house foundations, walls, churches and water mills.

Aerial drone photography piloted by computers were used to thermally scan the landscape and take overhead pictures.

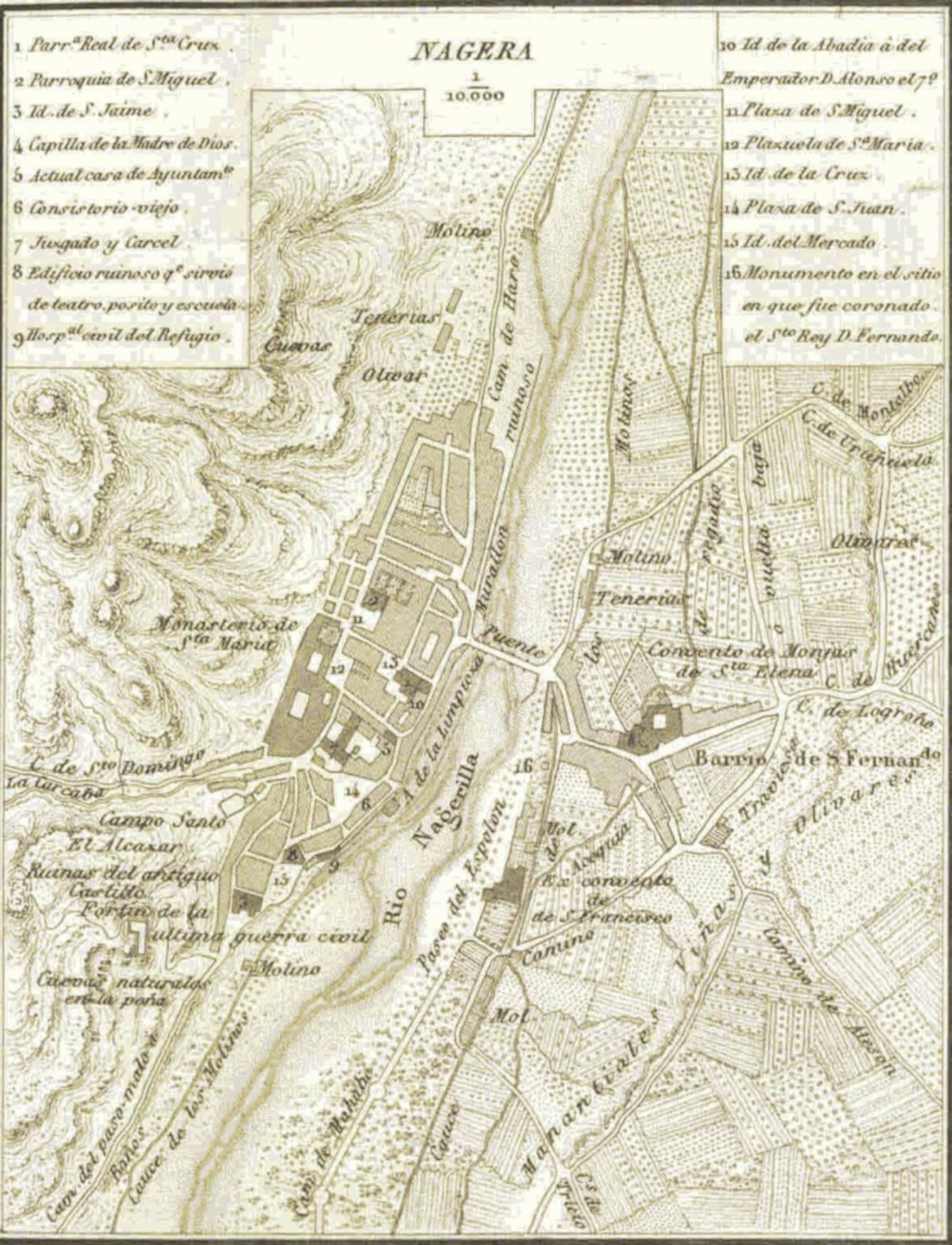

The Najerilla Valley Research Project team used historic maps, like this map of 1851 Najera, to find extinct structures and geographical features.

Historical maps were studied to find elements and features of the city that no longer exists. Brestian said many of these maps were found hanging in local bars.

In one example, the team lined up aerial photographs with a 1950s property map to find an overgrown 12th century water mill that would not have been found otherwise.

A geographical information system (GIS) was used to make digital landscapes and store the information. National Geographic defines GIS as “a computer system for capturing, storing, checking and displaying data related to positions on Earth’s surface.”

Fieldwork has ceased for now and Brestian's team has begun creating a 3D rendering of the medieval city using the data gathered.

There is some guesswork when it comes to recreating structures like the medieval houses, Brestian said. The team uses old drawings of churches and houses from the same time period to design 3D renderings of those structures.

San Vicente de Valle

The second area of study was San Vicente de Valle -- a town East of Najera with a total of four permanent residents.

The team set out to study the history of a building called the Church of the Assumption, whose caretaker nearly burned it to the ground in 1992 trying to rid its walls of ivy, revealing ancient artifacts and the original foundation.

It was later discovered that Roman gravestones were used to build the church, but no one knows where they came from since there is no city or farm, Brestian said.

After returning to Central Michigan University, Brestian began creating 3D models of the artifacts to use for study.

The original models were made from plastic, but to get a sense of weight and heftiness, molds were used to make models from sandstone.

"It is important to get a sense of the artifacts as objects," Brestian said.

An exhibition titled "Fragments of the Past" will showcase the 3D models from Brestian and his team's project in the University Art Gallery Oct. 26 through Nov. 17.