CMU neuroscience labs use rats, mice for developing new treatments

Animal activists disagree on use of animals in labs

Doctoral student John Gallien works on slicing brain on April 9 in the College of Health Professions Building.

Animal testing is a controversial topic.

Researchers like College of Medicine faculty Julien Rossignol believe the testing is necessary to develop new treatments for diseases.

However, animal rights activists like Westland junior McKenna Wietecha feel it is inhumane to test on an animal that cannot give its consent.

Rossignol leads research on mice and rats at Central Michigan University in hopes of developing treatments for Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, Alzheimer’s, strokes and brain tumors.

He said that he loves animals, and even has his own cats and dogs. However, that doesn’t change the fact that he believes using animals in labs as models for human beings is necessary. Rossignol explained that testing typically will start on cell cultures. If there is success with cell cultures, then his lab will move the treatments to animals because they serve as a medium ground between cells and humans.

“We don’t go from a cell result to testing on human," Rossignol said. "It’s not because my cells are better that a human will do better. The animal is a good application to that.”

But according to Wietecha, there needs to be a better middle-ground step because often times scientific results from animals do not translate equally to humans.

“Test results from non-human animals do not always transfer over to human results, so something that can harm a non-human animal might not harm humans and vice versa,” Wietecha said.

Reed City, post-doctoral CMED researcher Melissa Andrews explained that there will never be a “magic bullet” with medicine, meaning one drug or treatment will never help everyone in the exact same way. Therefore, even if there is a gap between animals and humans, there could also be a gap in drug response from human to human.

Wietecha suggested that substitutes for animal testing could include utilizing lab-made organs, accepting human volunteers if that is legal or taking advantage of technology and using computerized models.

Rossignol does not see these solutions as an option in this lab because there are no models out there that perfectly simulate how a body will respond to a treatment or drug. He said that he would use a model over animal testing if he felt that was an option.

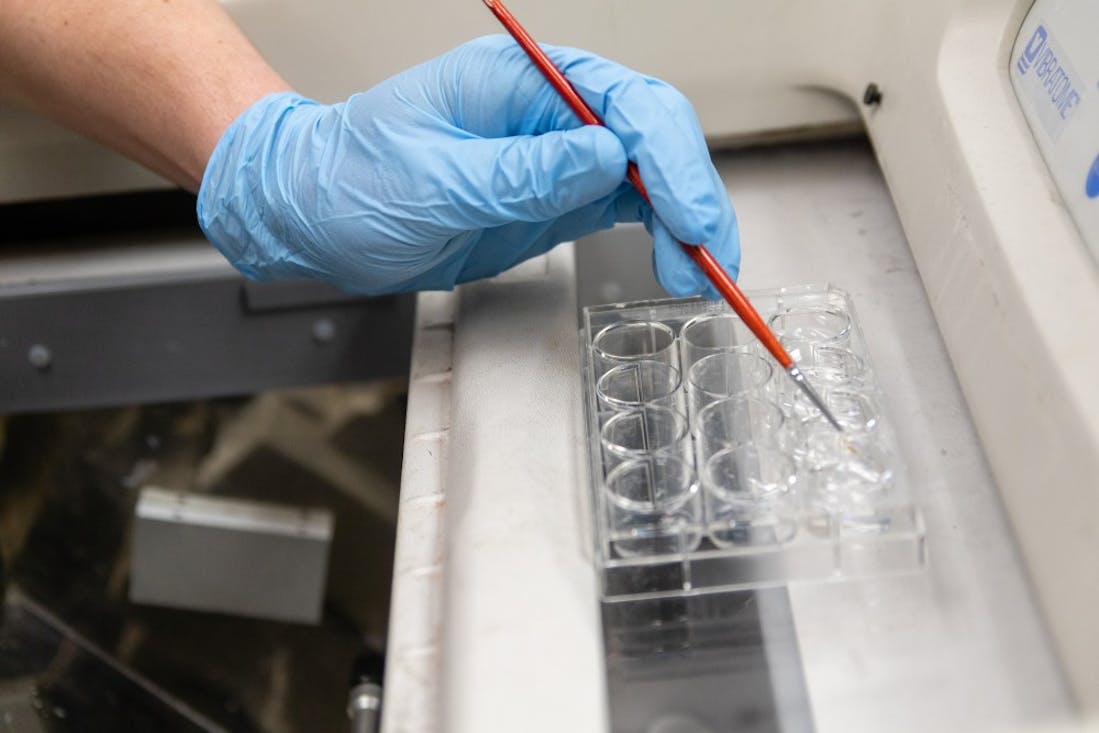

The brain samples are put into a solution after being sliced on April 9 in the College of Health Professions Building.

Andrews said that, in Rossignol’s lab, they follow very strict guidelines for the rats, and they get these guidelines from the Internal Animal Care and Use Committee.

The guidelines and standards they must follow include constant food and water for the animals, a social environment and enrichment toys for the animals to play with. The regulations also incorporate training any person working in the lab must go through to handle the animals.

IACUC checks CMU's labs every few months, and if they are not following code, then they can be shut down. Rossignol explained that it is in researchers' best interests to keep the animals healthy and in a good environment because if the animals die, then they lose months of work.

“If I am not taking care of the animal, any result that I have I won't be able to use it because that is my experiment,” Rossignol said. “That’s why I am very careful about what really we do with the animals.”

A slide with 30 micron slices of rat brain on April 9 in the College of Health Professions Building.

Rossignol feels that there is often a portrayal with animal testing that researchers are torturing the animals, but he said that is not the case. Therefore, he said he works to be completely transparent about his lab.

In order to be able to test these treatments on the rats, Rossignol and his lab team do need to give the rats a stroke or edit their genes, so they have the target disease. Then, Rossignol explained that they observe their behavior over a period of time that could be all the way up to sixth months. Finally, once they have collected behavioral data, they euthanize the animals and extract the brain, which they very thinly slice and analyze under microscopes.

Rossignol said that his work here at CMU in 2010 actually got accepted to go to clinical trials, so he sees the promise in his work now and believes it is necessary.

Wietecha said she understands that testing can lead to advancements in science; but at what cost?

“Humans should go about looking at non-human animals as just one of us, just a little bit different, because at the end of the day, we are all living beings,” she said.