You are Not Forgotten: How a CMU network is organizing a "community of memory" for the Korean War

The black and white POW/MIA flag is raised on Sept. 18, 2021 outside Warriner Hall. Courtesy Photo | Hope Elizabeth May

On Friday, Nov. 5, American and Michigan flags were lowered to half-staff across the state.

The sunken flag symbolizes the short but impactful life of John Shelemba, born and raised in Hamtramck. It also represents years of work to bring him home from a forgotten war.

"On behalf of the entire state of Michigan, I thank Army Pfc. John Shelemba for his service and sacrifice to our nation,” said Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. “We are grateful to finally have him home. My thoughts are with his loved ones as he is laid to rest.”

Those efforts eventually gained support at Central Michigan University.

For the last two years, Philosophy Professor Hope Elizabeth May and Trenton junior Michael Buzzy have brought Prisoner of War/Missing in Action activism to campus with a weekly podcast, "Virtues of Peace," educational events and an annual day of recognition.

It was May, Buzzy and other collaborators who sent a letter to Whitmer’s office in September requesting that the flags be lowered.

Years of work will finally pay off Thursday but to fully appreciate the undertaking, you need to understand the Hamtramck boy’s story from the beginning.

Who was John Shelemba?

Sometime in 1948, a blue-eyed, 130-pound boy named John Shelemba enlisted in the U.S. Army. He was the son of an Austrian immigrant who had moved to Michigan after World War I. The 17-year-old was eager to serve.

His life and military career were cut short by the Korean War.

Shelemba served in Company: L, 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment. He went missing in action on July 20, 1950, during his unit’s defense of Taejon, South Korea.

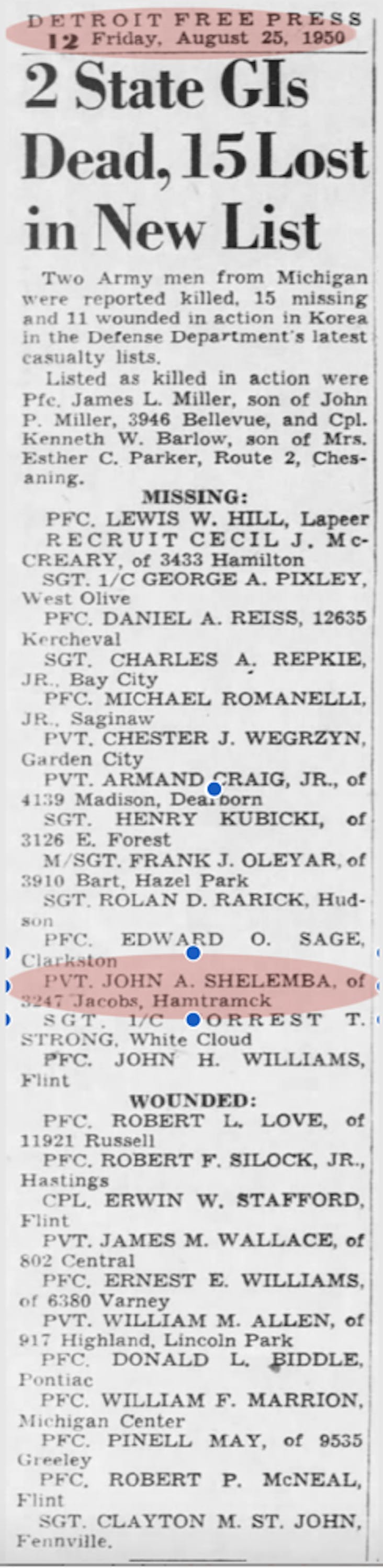

A story published in the Aug. 25, 1950 edition of the Detroit Free Press would be the last anyone would hear of him – including his family.

A story published in the Aug. 25, 1950 edition of the Detriot Free Press show's Shelemba listed as MIA along with other service members. Courtesy Photo | Hope Elizabeth May

One of Shelemba’s last living relatives is his half-niece Michelle Vance. Today, she thinks about the 60+ Veterans' Days she and her family could have remembered him.

“There was no talk in our family at all about John,” Vance said. “I think what had happened is they were just so grief-stricken; nobody ever even talked about what happened.”

Following the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement on July 27, 1953, the American Graves Registration Services was tasked with recovering the remains of American casualties lost in South Korean battlefields.

Shelemba’s remains were recovered, but without dog tags his skeleton provided little help in identification.

For more than 50 years his bones laid nameless at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, also known as the “Punchbowl Cemetery” in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Instead of a name, the remains had numbers: “Unknown X-251 (from Taejon).”

In October 2018, Shelemba’s bones were some of the first to be exhumed as part of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency’s (DPAA) Korean War identification program. For the next several months, the remains were under the care of forensic anthropologist Jennie Jin.

It took about a year of lab analysis for Jin to answer three important questions. Who was Unknown X-251? Where did he come from? Who is left to remember him?

“We had to do a lot of historical research to see if that was the case, to see who this could be?” Jin said in “Virtues of Peace” on Nov. 19, 2020.

On Sept. 12, 2019 Jin and her team found their answers.

They used dental, anthropological and radiograph analysis to identify Shelemba's remains. In the end, Jin said an irregularity in the clavicle bone was the last piece of evidence they needed to give Shelemba his identity back.

Getting the Call

When Michelle Vance was contacted by the DPAA about her missing uncle, she thought it was a scam.

She listened to the message left on her cell phone from a woman claiming to be from the U.S. army. Vance was intrigued, though, by how much information the woman had about her family.

“I told my husband that this woman knew way too much. He says, ‘oh, just forget about it,’” Vance said. “Well, I've been married 42 years, I don’t always listen to my husband.”

She called back. She was able to help the DPAA verify Shelemba’s lineage.

A DPAA press release from Dec. 30, 2019, made the news public: John Shelemba of Hamtramck, Michigan, who was killed during the Korean War, was finally accounted for.

Vance said she received a flood of condolences from military families across the country after posting the news on Facebook.

All from people she never met about an uncle she never knew existed.

The DPAA’s identification project was a lesson in empathy, Vance said.

“I have a son. Thank goodness there's no draft right now. My thoughts were if anything were to happen to him, I’d want somebody to do the right thing,” Vance said. “It’s not about closure for me, it’s about doing right by (John).”

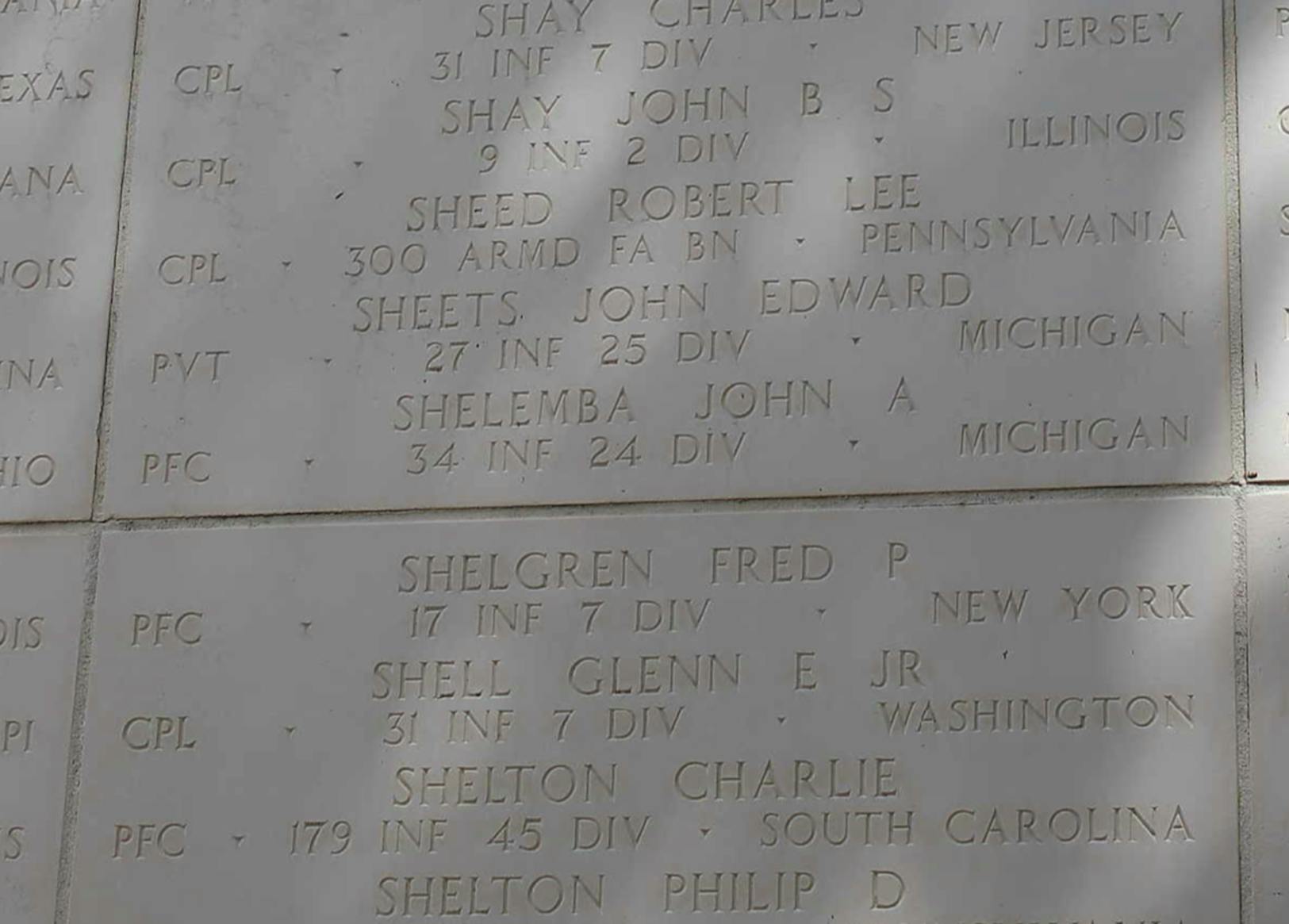

Shelemba’s name is recorded on the Courts of the Missing at the Punchbowl Cemetary, along with the others who were missing from the Korean War.

PFC John Shelemba's name appears on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, in Honolulu, Hawaii. Courtesy Photo

Receiving Recognition

For Buzzy and May, giving Shelemba his identity back was only part of the goal.

May is a tenured professor that engages in public-facing scholarship focusing on the peace through law movement. Buzzy is an honors student majoring in political science and philosophy. Together the duo works to create POW/MIA educational materials for the CMU community.

It was at their request that CMU began celebrating POW/MIA recognition day in September 2020. The event featured a ceremonial raising of the black and white flag.

After hearing about Shelemba’s reidentification from a 2019 news article, Buzzy and May decided to localize the universal issue.

They invited Vance and Jin to talk about Shelemba’s story on their podcast, “Virtues of Peace” which is all documented on May’s website.

“It’s stories like Shelemba that I've found immense meaning in,” Buzzy said. “These stories have helped me battle my own adversities in life.”

There are plenty of stories to choose from. According to the DPAA website, nearly 8,000 Korean War service members are still unaccounted for.

The state recognized two in August by lowering flags. Their names were Sgt. Jessie D. Hill and Cpl. Dale W. Wright. Both were Korean War veterans like Shelemba. Buzzy and May wondered why he had not received the same honor.

“(Lowering the flags) sends a strong message to POW/MIA family members of all wars; be it WWII, Korean, the Cold War or Vietnam,” said Marty Eddy, lead coordinator for the the League of POW/MIA families in Michigan. “It says that the state of Michigan recognizes the sacrifice and pays tribute and honor to the service member.”

Buzzy and May made it their mission to give Shelemba the same tribute.

Buzzy wrote a six-paragraph letter to Whitmer's office earlier this semester. Writing the letter was easy – getting it through the state capitol bureaucracy was not.

“We sent the letter through every channel we possibly could hoping something would get through,” Buzzy said.

After getting signatures from CMU President Bob Davies and Director of CMU’s Veterans’ Resource Center Duane Klienhardt, the letter made its way through the Governor’s portal, the office of Rep. Abraham Aiyash and the hands of lobbyist groups.

Near the end of October, May finally got the answer she and Buzzy had been waiting for.

The letter sent to Gov. Gretchen Whitmer requesting flags be lowered to honor John Shelemba was written by Michael Buzzy and Hope Elizabeth May.

The flags were lowered in Shelemba’s name the day after his public funeral which is at noon on Thursday, Nov. 4 at the Great Lakes National Cemetery in Holly.

He was laid to rest with full military honors.

The effort was about putting policy into practice, May said, about using individual stories to examine a widespread issue and addressing the United States’ most overlooked war.

“I call it leveraging history," May said. "You find a moment, or a symbol, that many different stories can coalesce into one thing.”

The DPAA is the only government agency tasked with finding and identifying missing soldiers from past conflicts dating back to World War II.

According to their data, there are about 80,000 U.S. service members from past conflicts who remain unidentified.

For Pfc. John Shelemba, his journey is now at an end and he can rest in peace.

"Grandpa, Uncle Johnny is finally coming home," Vance wrote on Facebook after receiving the call from the DPAA. "I have goosebumps. I am eternally grateful to the Department of Defense and the army who never gave up in their search."