Author, doctor reflects on uncovering Flint water crisis

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha details first-hand experience with government mistrust, promotes advocacy

A collaboration across campus brought Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha to Warriner Hall for Water Justice, an event speaking on Flint's water crisis, vaccine hesitancy and civic engagement.

Plachta Auditorium was packed with students Wednesday night as Hanna-Attisha recounted her experience discovering the Flint water crisis and how it related to a greater sense of distrust in science.

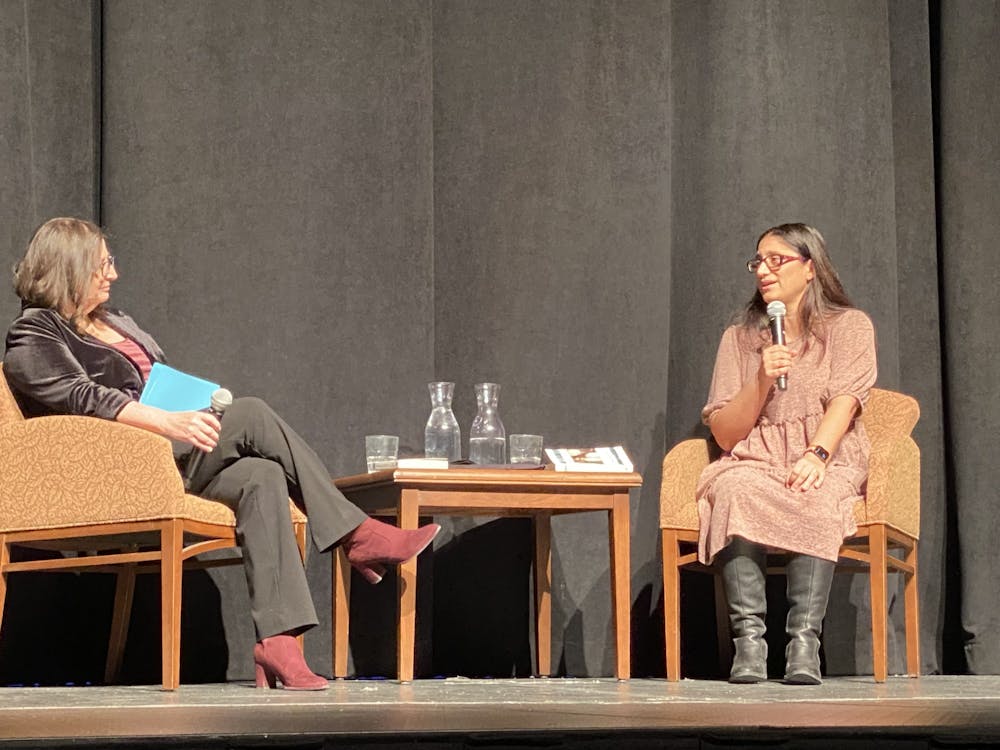

Discussions were moderated through professor of anthropology, Cathy Willermet. In the final portion of the presentation, students in the crowd were able to ask their own questions.

Hanna-Attisha played a critical role in discovering the Flint water crisis by noticing increased levels of lead in children.

The crisis arose when Michigan switched the city's water source from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the Flint River in 2014, unknowingly leaving the community with dangerously high levels of lead in the water.

“Flint’s water crisis wasn’t the first, it wasn’t the worst and it wasn’t the last,” she said.

Hanna-Attisha said she believes there were people who contributed to the crisis happening, but other larger factors overshadow that.

"There are lots of villains in this story, a disaster of this scale does not happen by accident," she said. "The real villains are harder to see because the real villains live underneath the behavior. The real villains are the ongoing effects of racism, inequality, greed, anti-intellectualism and even laissez-faire neo-liberal capitalism."

She also discussed the long term implications of the crisis. She advocated for people to invest in the community of Flint, as she said people living there will need help in the years to come.

"What about all these things that we need to do for kids for 20 years," she said. "They're going to need literacy services, tutoring, home visiting, breastfeeding support, mental health care and trauma-informed services."

Hanna-Attisha shared a story of a Flint family, as an example, who lived in the area for generations after moving there to find opportunity. One of the great-grandsons drank the contaminated water and subsequently suffered major health issues.

“For some folks, that crisis will never go away, and for some folks, no matter what you tell them about water quality, they will never drink that water again,” she said.

Hanna-Attisha said the effects of shortcomings in public health policy, especially with environmental issues, are felt most in underrepresented communities.

“Contamination is not born equally, there are certain communities, specifically communities of color, that disproportionately bear the burden of environmental contamination,” she said.

Hanna-Attisha said government officials have historically sown distrust of medicine - and vaccines - into underrepresented communities. The Flint water crisis was no exception.

"Why should you take a vaccine when you tell me my water is safe and it wasn't safe," she said.

Hanna-Attisha said she has witnessed this distrust first-hand from some of her patients over the years. She said parents that were hesitant when it came to vaccines used to be willing to talk about the choice.

But more recently, that has changed.

Now, she she calls some patients “vaccine-resistant" because they are sternly against the idea, regardless of discussion.

“It is frustrating obviously, but sometimes that frustration is a pick-me-up,” she said. “(Talking with them) didn’t work, let’s try and figure out what we can do about it.”

She also said some patients are given misinformation about vaccines and medicine that are difficult to argue with.

"This has been a long-standing attack on science," she said.

She encourages patients to be critical thinkers and ask questions. She also said health professionals need to be able to answer those questions and invest time into gaining their patient's trust.

"So (relationship building) is often how it works with vaccine hesitancy and it takes time; it takes trust," she said. "It takes humility, to be able to stand shoulder to shoulder and spend time to answer legitimate questions."

Above all else, Hanna-Attisha said she is an advocate for positive change.

She believes younger generations are leading the charge for change but said she understands the number of issues can be overwhelming. To help, she offered tips for those who want to work in advocacy.

"Find your passion, find your (people), stay persistent and be prepared," she said. "When you want to solve a problem out there in the world, it's not going to be neatly divided into university departments. You need to have this multidisciplinary perspective and have all kinds of different friends because when you have that diverse lens, you ask different questions and come up with different solutions."

The event was brought to the campus by:

- Mary Ellen Brandell Volunteer Center

- CMU Program Board

- Eta Sigma Gamma

- Residence Housing Association

- Sarah R. Opperman Leadership Institute

- College of Medicine

- Residence Life

- CMU Honors Program

- College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences