CMU professor research findings will be used for cancer study

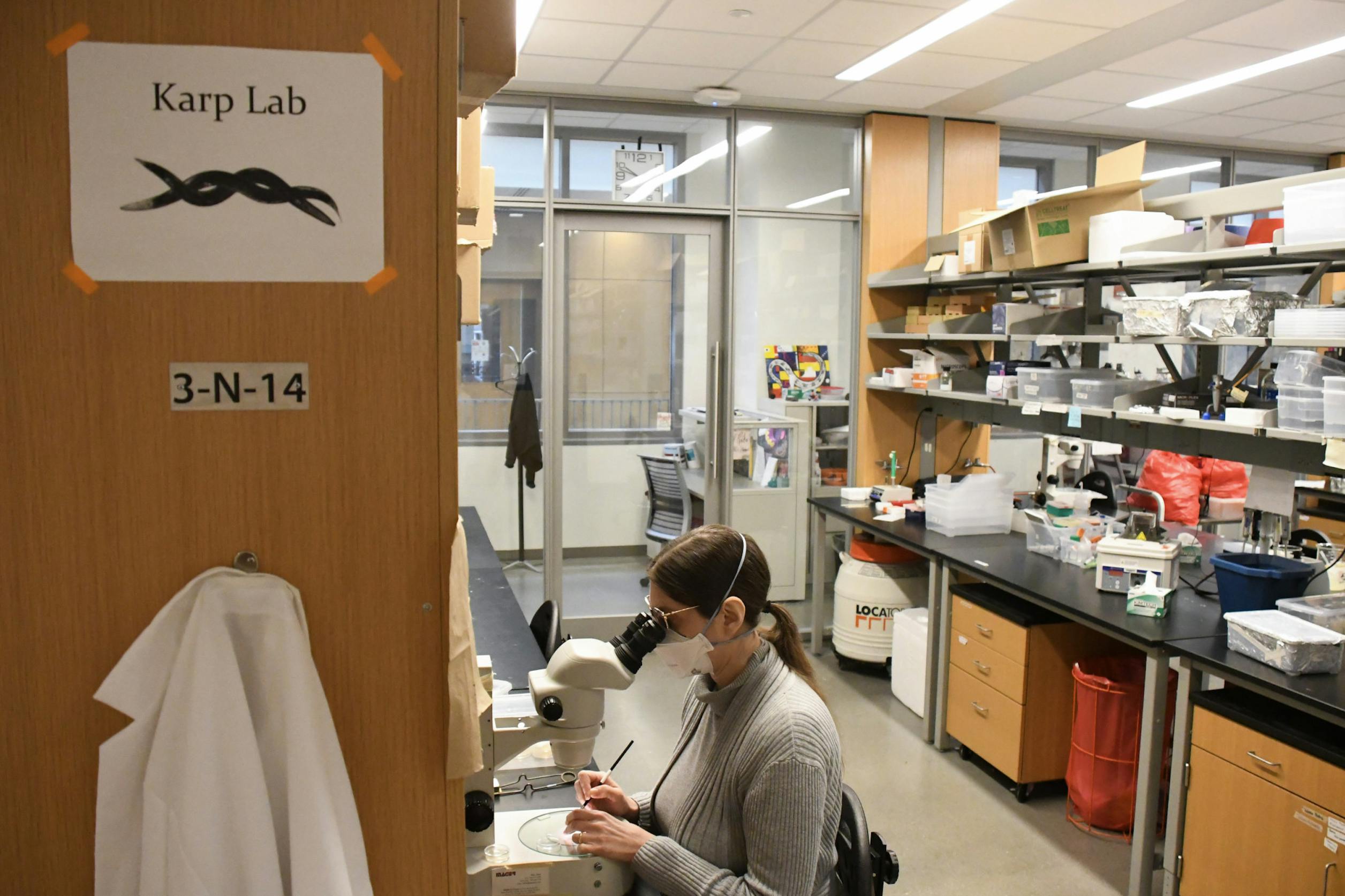

Dr. Xantha Karp looks through a microscope in her lab Monday, Jan. 29 in the Biosciences Building. (CM-Life | Ella Miller)

Imagine if a scientific breakthrough that could be used for cancer research was discovered right in your backyard. For Central Michigan University students, their backyard is Xantha Karp’s research lab here on campus.

Karp, biology and genetics professor at CMU, is the principle investigator for a research project working with microscopic roundworms, or a tiny species of worm. The project is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for three years. This is Karp and her students' first year working on the project with the grant money.

Before coming to CMU, Karp received her bachelors degree double majoring in human biology and anthropology at the University of Toronto in Canada. There, she worked on undergraduate research with frog embryos to study how proteins outside of a cell can influence a cell’s development.

“What I really loved, is these frogs … you could fertilize (their) eggs in a dish, and the embryos were big enough that you could just watch with your naked eyes and see the cells dividing,” Karp said.

Dr. Xantha Karp trains CMU junior Rachel Atterberry to do work in her lab Monday, Jan. 29 in the Biosciences Building. (CM-Life | Ella Miller)

She then went on to Columbia University in New York for a doctoral degree in genetics and development. Afterwards, she completed post-doctoral research at Dartmouth College and the University of Massachusetts Medical School with Dr. Victor Ambros.

Her postdoctoral research included working with the same roundworms she uses in her research at CMU now, Caenorhabditis elegans, or C. elegans. There, Karp worked to discover how communication between two specific stem cells works to form part of the reproductive system in C. elegans. It was in this research that Karp said she found her inspiration for continuing to work with C. elegans.

C. elegans are a model organism used in many scientific studies because they are an “accessible system”, according to Karp. Karp said with C. elegans, researchers are able to look at the individual cells in the transparent organism, unlike they could with mammals.

Karp and her team of graduate and undergraduate students at CMU are looking at the worms to investigate the dauer stage of stem cells.

What are stem cells? According to the NIH, stem cells are cells in a living organism that can further specialize in a body so they are able to perform specific functions. For example, human skin cells act as a barrier against ultraviolet rays from the sun to protect the rest of the organs in a body. Cells that make up the heart, in turn, would not be coded to protect from UV rays.

What is dauer?

Dauer, according to Karp, is a reversible, non-proliferating state in which a cell can reside.

“There’s genes that are required for (the worms) to develop normally under standard lab conditions, where they have lots of food, and so forth,” Karp said. “But if the worms are in poor conditions, they can interrupt their development … with this stage called dauer.”

Poor conditions could look like high heat, lack of food resources or crowding of too many worms in one habitat.

Dr. Xantha Karp trains CMU undergraduate students studying biology, neuroscience and other related majors to work in her lab Monday, Jan. 29 in the Biosciences Building. (CM-Life | Ella Miller)

Karp said that the post-dauer stage is what fascinates her, because these cells are able to pick back up right where they left off.

“For example, blood stem cells need to be able to produce all the different blood cell types -- red blood cells, white blood cells,” Karp said. “But they also need to be sure not to produce anything that’s not blood. We don’t want blood cells making nerve cells or muscle or skin. So staying at that precise place is called multipotency.”

However, they don’t continue development with the same genes they were using pre-dauer.

“If (the cells) start their development again, it seems to be different genes that are important,” Karp said. “So the cells are developing, they have the same kind of developmental outcome at the end, so they do the same things, but there’s different genes helping them get there depending on if they have developed continuously straight through in good conditions, or if they have this interruption.”

Karp’s lab, in essence, works to figure out how these cells know to continue doing what they need in order to function properly after recovering from the dauer stage.

How could this be related to cancer research?

While the current research is being conducted on worms, that’s not to say that findings won’t be used in the human medical field.

“Because the genes that we are studying have homologues in humans and other organisms, we think that what we’re learning is going to be applicable (in humans),” Karp said.

Dr. Xantha Karp assists CMU junior Rachel Atterberry as she participates in training to work in Karp's lab Monday, Jan. 29 in the Biosciences Building. (CM-Life | Ella Miller)

The fundamental goal of this lab, Karp said, is to get an understanding of how this dauer stage works. In conjunction, the results from this lab will be applied to cancer research with Stave Kohtz, a professor of pathology at CMU.

Itzel Gutierrez, a graduate student in the lab, is currently working in collaboration with Kohtz.

Gutierrez said it is the research team's hope that the genes being studied in the worms in Karp’s lab are similar to the genes in human breast cancer tumors. And so far, their findings indicate a positive correlation between the two.

According to Gutierrez, breast cancer cells going into dauer is what is commonly known as remission. If a patient is diagnosed with cancer but later on is considered to be “in remission,” the cells in the cancerous tumor are in a non-proliferating state where they do not grow and multiply.

Gutierrez said the ultimate goal with their research is to study what enables these cancer cells to stay in dauer, therefore maintaining the patient’s stage of remission to ensure the cancer does not come out of remission.

Dr. Xantha Karp examines under a microscope in her lab Monday, Jan. 29 in the Biosciences Building. (CM-Life | Ella Miller)